Sandro Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” was inspired by an exiled poet. Forced to spend the last 10 years of his life away from home, Ovid never gave up writing. His exilic works show readers the power of literature to forge hope from suffering.

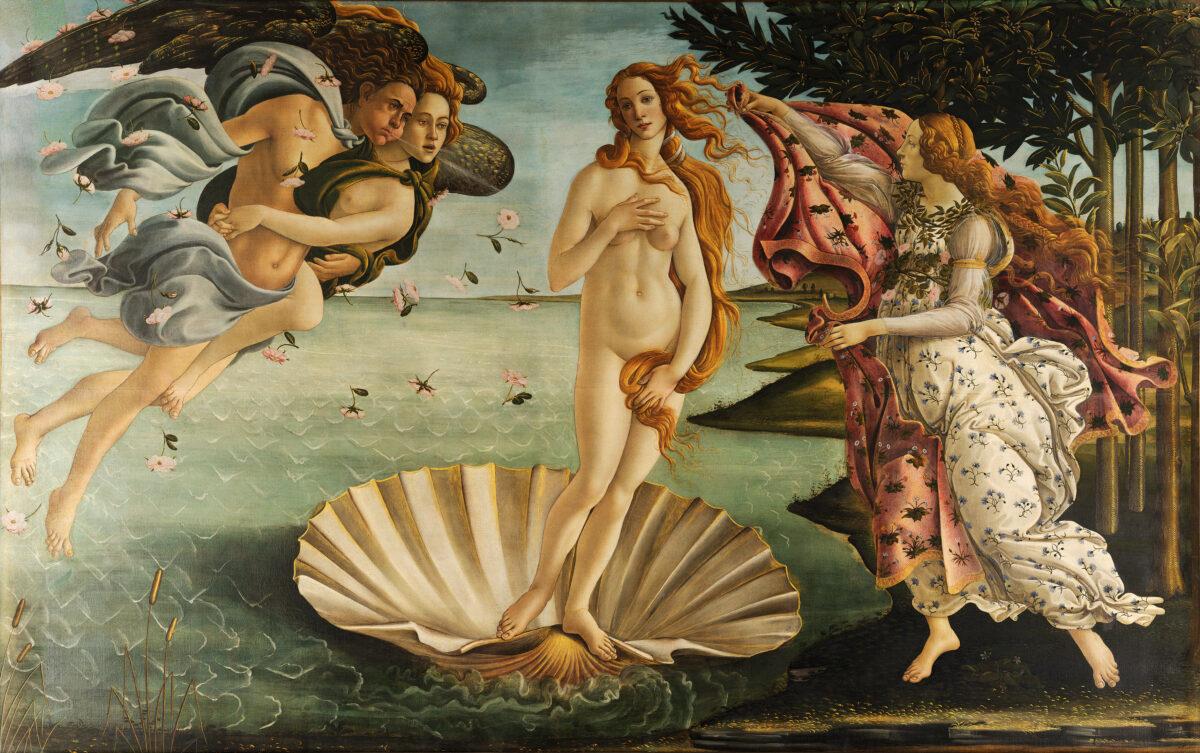

"The Birth of Venus," circa 1485, by Sandro Botticelli. Tempera and plaster on canvas.

Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Public Domain

Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Public Domain