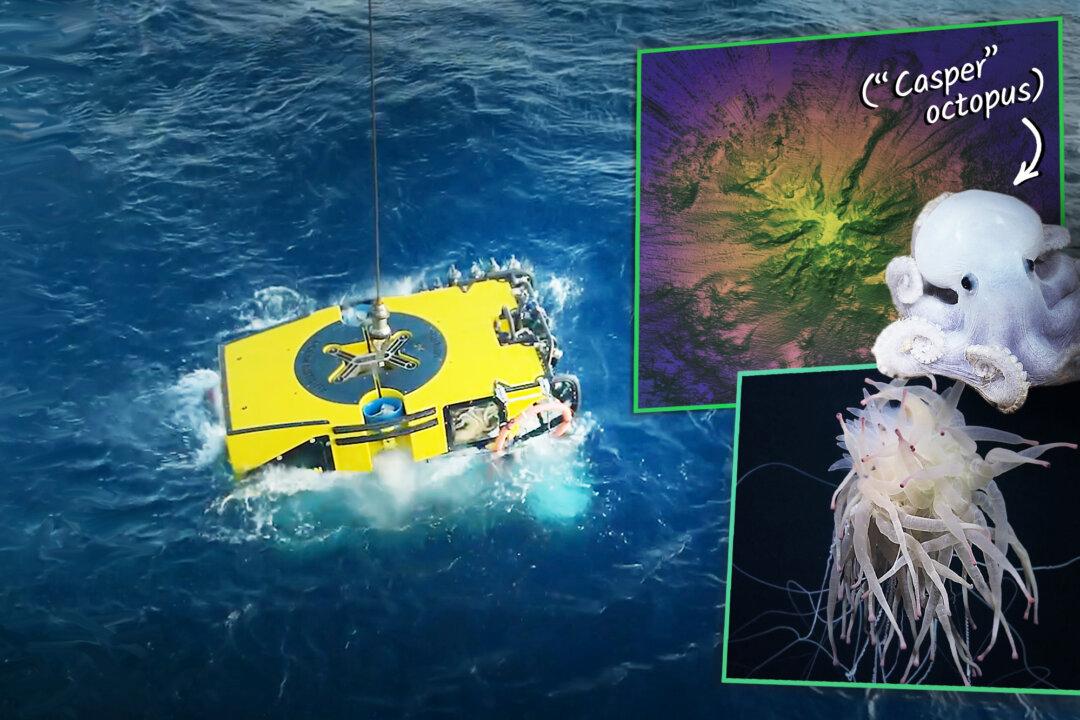

A remote-controlled deep-sea robot detected groves of sponge gardens and ancient coral submerged thousands of feet under the Pacific Ocean. This hidden ecosystem was videoed for the first time thriving on a newfound underwater mountain—or seamount—off the western coast of South America.

On an oceanographic voyage, a team of researchers led by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, founded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt, announced they had discovered this seamount along an underwater chain of mountains called the Nazca Ridge, 900 miles off the coast of Chile.