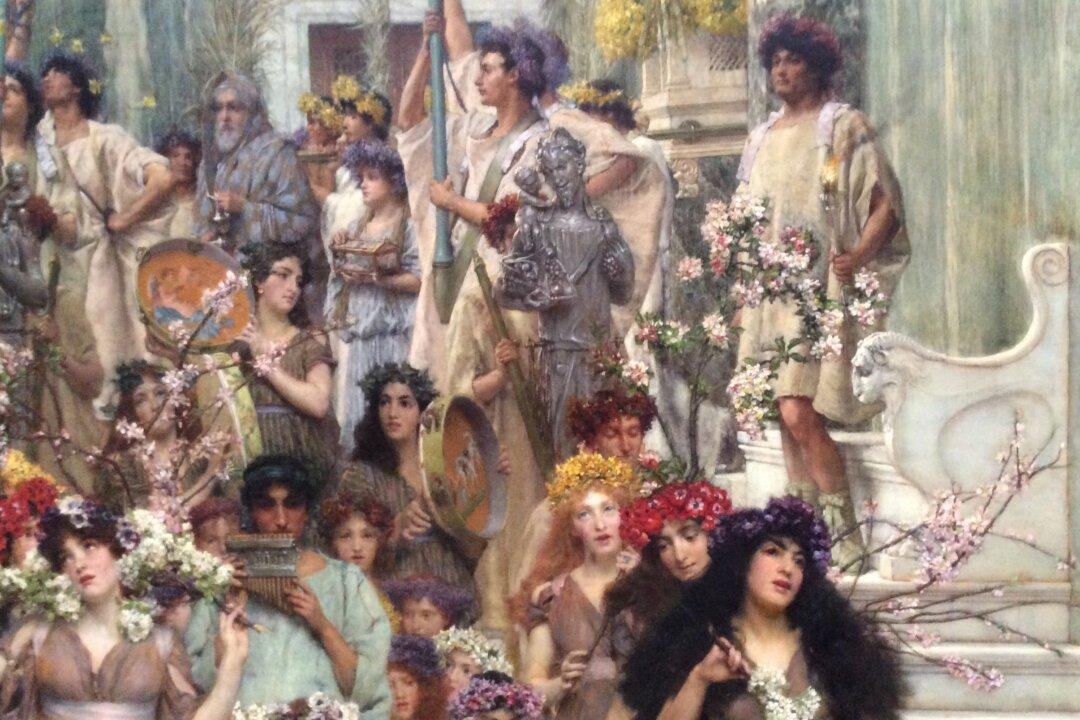

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck gives us a master class on filmmaking with his stunning Oscar-nominated release “Never Look Away.” The latest offering by the award-winning writer and director is everything a movie should be: a compelling story, visually sublime, conceptually evocative, and emotionally gripping.

The film follows an aspiring artist over three turbulent and dynamic decades of German history: the 1930s into the ‘60s, examining how the political ideologies during this era affect one family in particular.