Ridley Scott is one of the cinematic kings of visual spectacle, and in that sense, his biopic “Napoleon” is on par with anything he’s ever made.

‘Napoleon’: Why You Should Wait for the 4-Hour Version

Visually sumptuous but disjointed and lacking power because Ridley Scott had to cut his 4-hour version down to 2 hours.

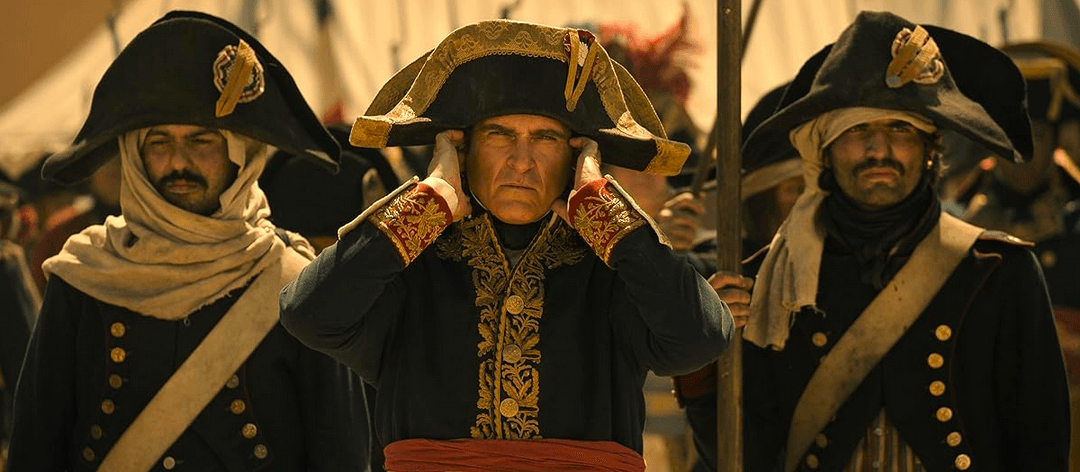

Napoleon Bonaparte (Joaquin Phoenix, center) covers his ears during canon fire, in "Napoleon." Aidan Monaghan/Apple

Mark Jackson is the senior film critic for The Epoch Times and a Rotten Tomatoes-approved critic. Mark earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from Williams College, followed by classical theater conservatory training, and has 20 years' experience as a New York professional actor. He narrated The Epoch Times audiobook "How the Specter of Communism Is Ruling Our World," available on iTunes, Audible, and YouTube. Mark is featured in the book "How to Be a Film Critic in Five Easy Lessons" by Christopher K. Brooks. In addition to films, he enjoys Harley-Davidsons, rock-climbing, qigong, martial arts, and human rights activism.

Author’s Selected Articles