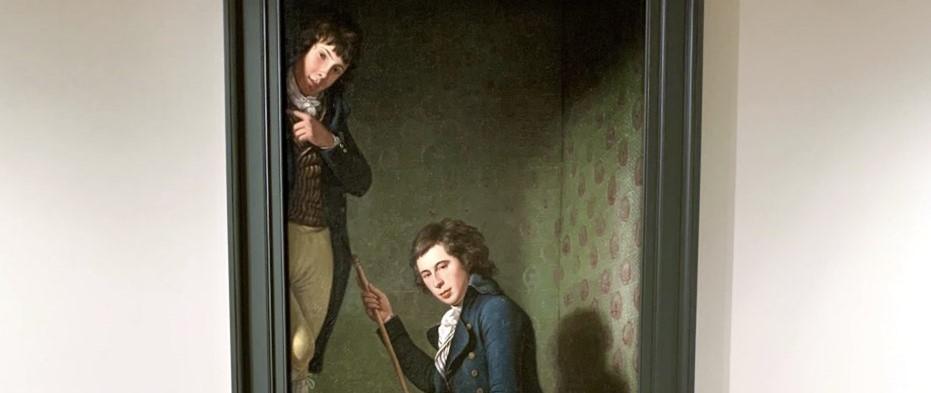

Perhaps today, you’ve come to admire paintings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. As you walk down a hallway, you see two boys walking up a stairway, and you want to follow. You take the first step up. Then you realize you’ll get nowhere on this staircase.

You almost bump your nose against “Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale I),” painted in 1795 by Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827). Possibly the first trompe l’oeil (“trick the eye”) painting by an American artist, Peale’s piece has played a joke on many who want to take a closer look.