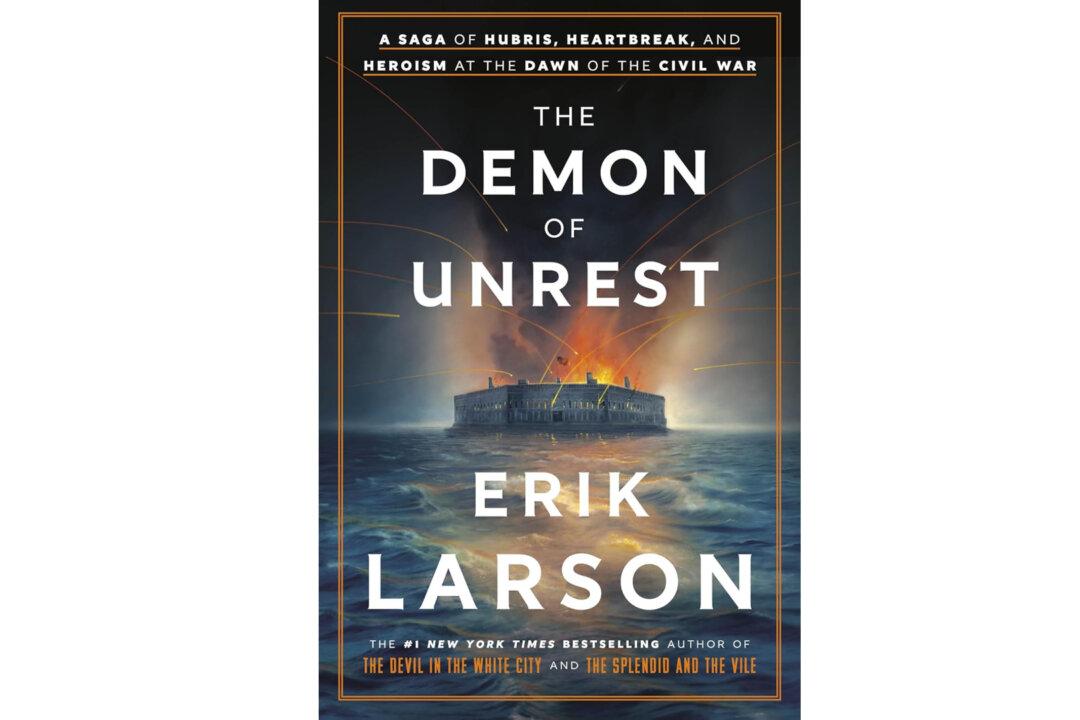

Author Erik Larson presents onion layers of reasons that Americans eventually warred against one another, in his new book, “The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War.”

Though a mouthful, the title hearkens back to the lengthy labels once attached to pre-20th-century books. It’s the main title—“The Demon of Unrest”—that serves as this history book’s thesis. The phrase is part of a quote by a lesser-known historic figure, Dennis Hart Mahan, a 19th-century professor at West Point. Larson includes the quote early on in chapter one: “A Boat in the Dark.” When writing to a friend in November 1860, Mahan used the term “demon of unrest” when referring to affluent planters affixed to a way of life steeped in slavery.