You may only have a few fresh ears per year, but chances are you still eat a ton of corn. It’s in almost everything. Corn plays a starring role in chips and cereal, but is more often a supporting player, functioning as a sweetener, oil, or starch.

Corn has been cultivated throughout the Americas for nearly 9,000 years. The Olmec, Maya, Aztec, and other pre-Colombian people built great civilizations on a corn-rich diet. Corn began with a wild grass, from which ancient farmers carefully developed varieties for superior taste and nutrition. Today we call these prized breeds heirlooms.

Over the last few decades, however, corn cultivation has taken a decidedly different turn. Advanced breeding methods have created hybrids with enormous yields, built-in pest resistance, and a greater concentration of sugars.

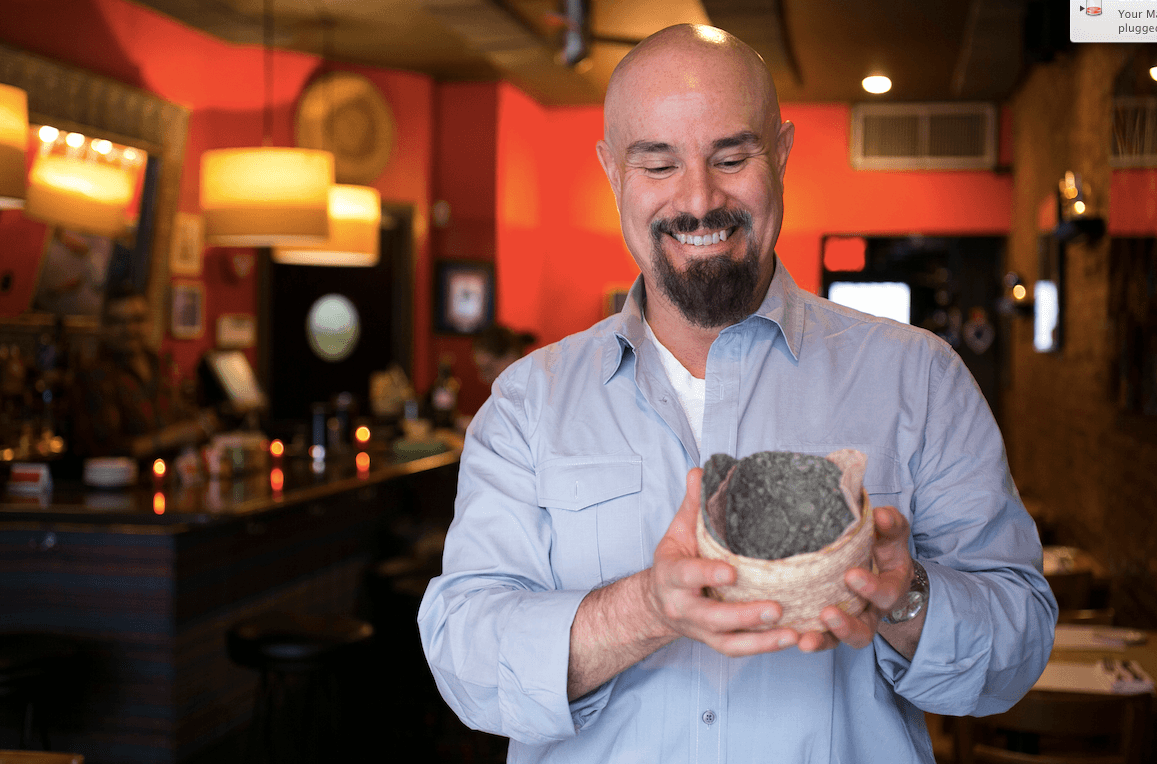

According to world-renowned chef Roberto Santibañez, these technological innovations have taken away something vital.

“Corn is no longer real food,” he said. “It is just a surplus of carbohydrates floating around the world.”

Ancient Corn

Santibañez is serious about corn. At Fonda—his farm-to-table Mexican restaurants in New York City—kitchens crank out about a million handmade tortillas a year. But unlike typical white tortillas made from conventional corn hybrids, Fonda’s may be shades of red or green, depending on the heirloom variety available.

“I don’t care what the color of my tortillas are any given day,” Santibañez said. “Even if you have a really, really small producer who only has a few bags, we buy them. We’ve been very successful with it. People are very happy.”