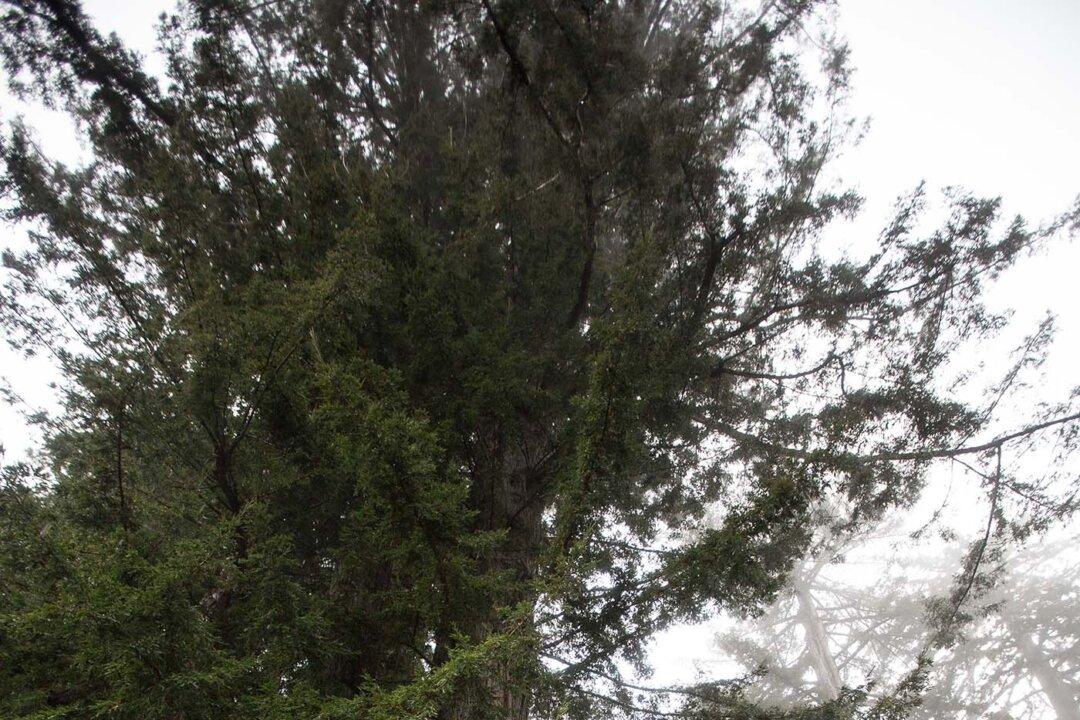

When the snow starts melting, magic starts flowing in this little grove of maple trees in southeastern Minnesota.

Since time immemorial, maple trees have been tapped for their sap harvests. Early Americans learned the practice from indigenous peoples hundreds of years ago. As the centuries passed, the sophistication of large-scale maple syrup productions evolved, but the harvesting at the heart of it all remains naught but simple tradition: the right weather and the right trees.