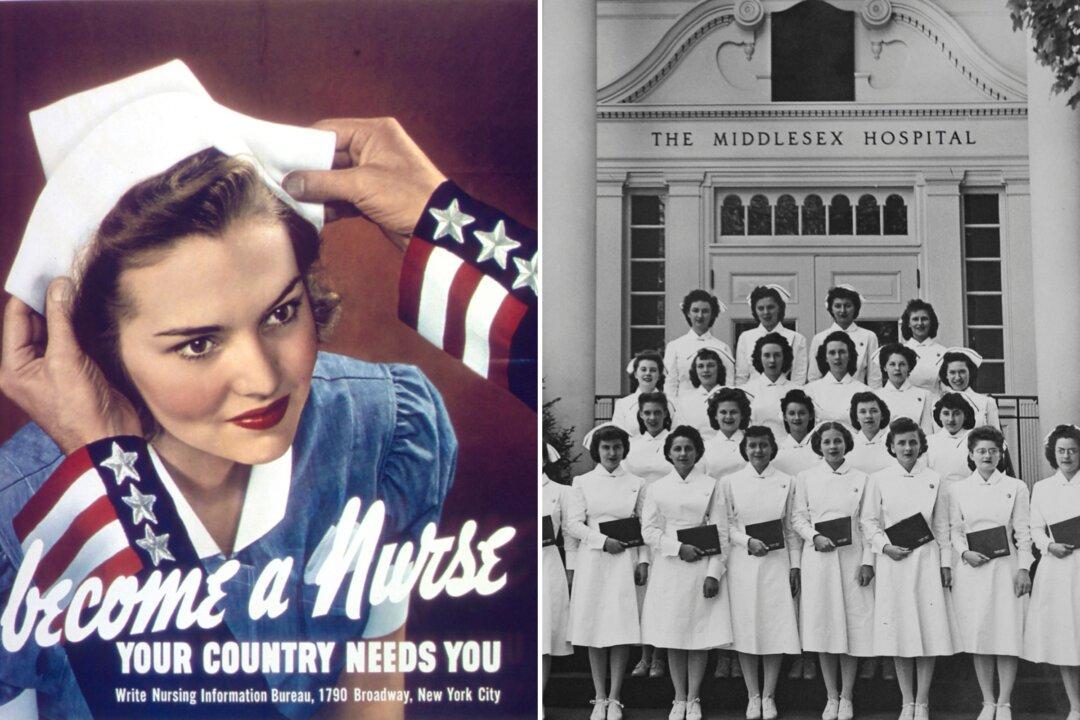

The United States had led the Allies to victory in World War II, and with the war over, members of “The Greatest Generation” looked forward to getting back to civilian life, making a living, and spending time with their growing families.

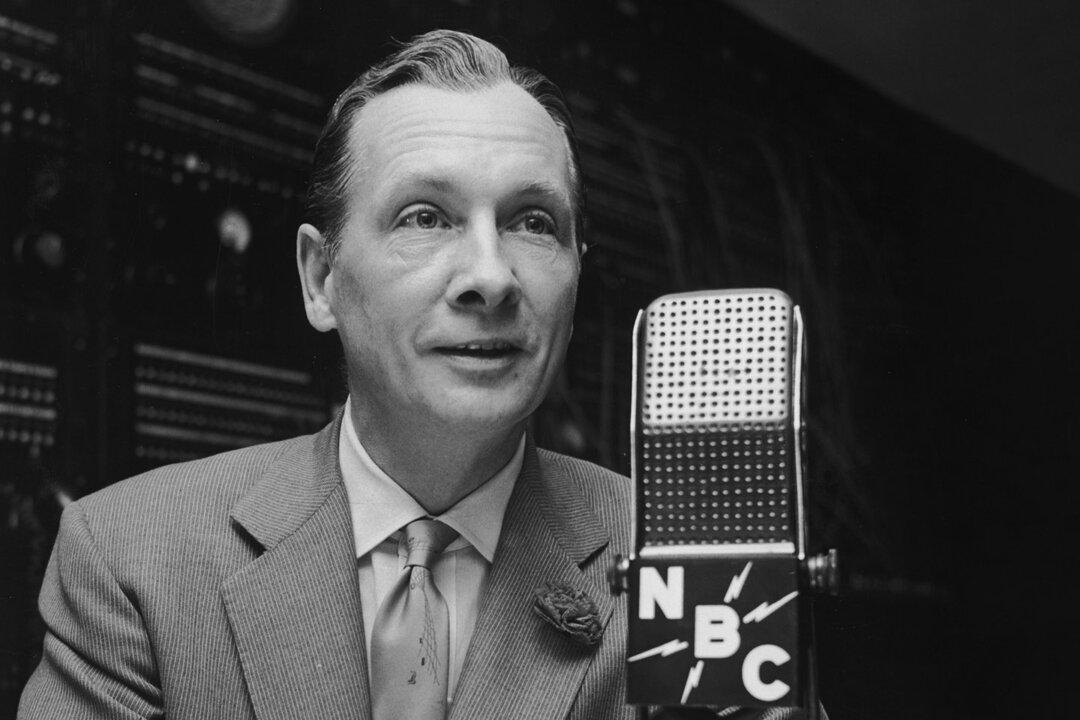

Jane Anderson Vercelli looks back on her early years growing up in Connecticut with great fondness. “It was an idyllic time. It was an idyllic childhood,” remembers the oldest child of American composer Leroy Anderson.