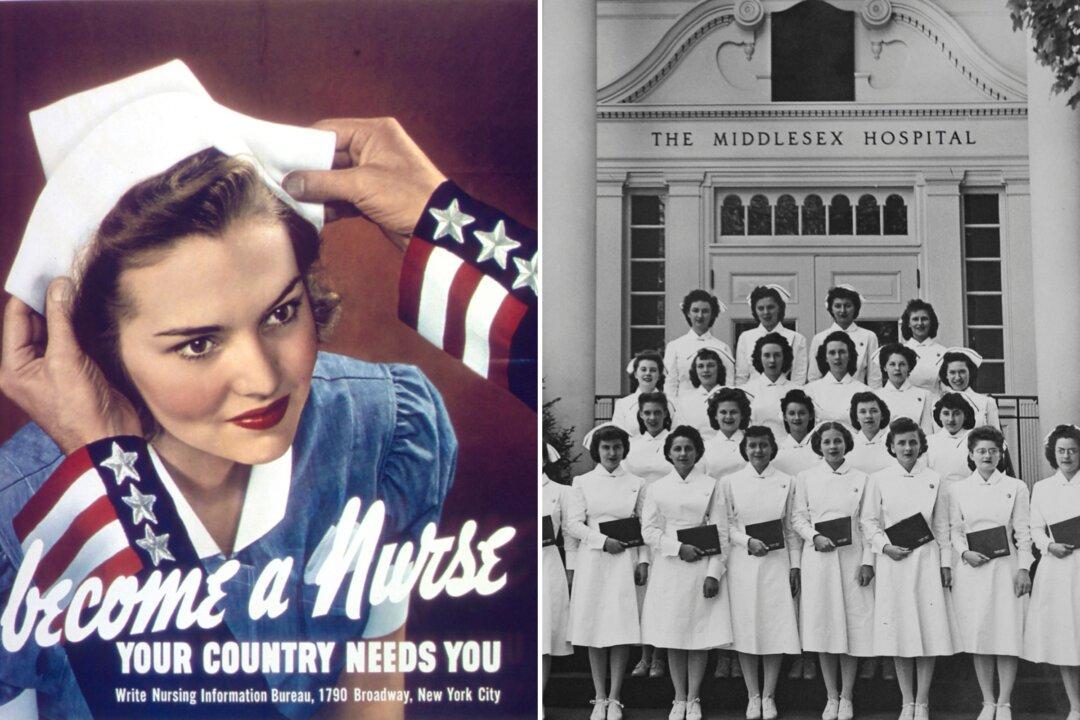

It was the start of the second half of the century. With the Allied victory in World War II and the departure of troops from Korea, America was on the move. The Baby Boom was on, suburbs blossomed, incomes for many Americans rose, and the “Sunday Drive” became a staple family activity. Along with medical breakthroughs like the polio vaccine and a landmark Supreme Court ruling on the integration of public schools, many Americans felt a sense of optimism.

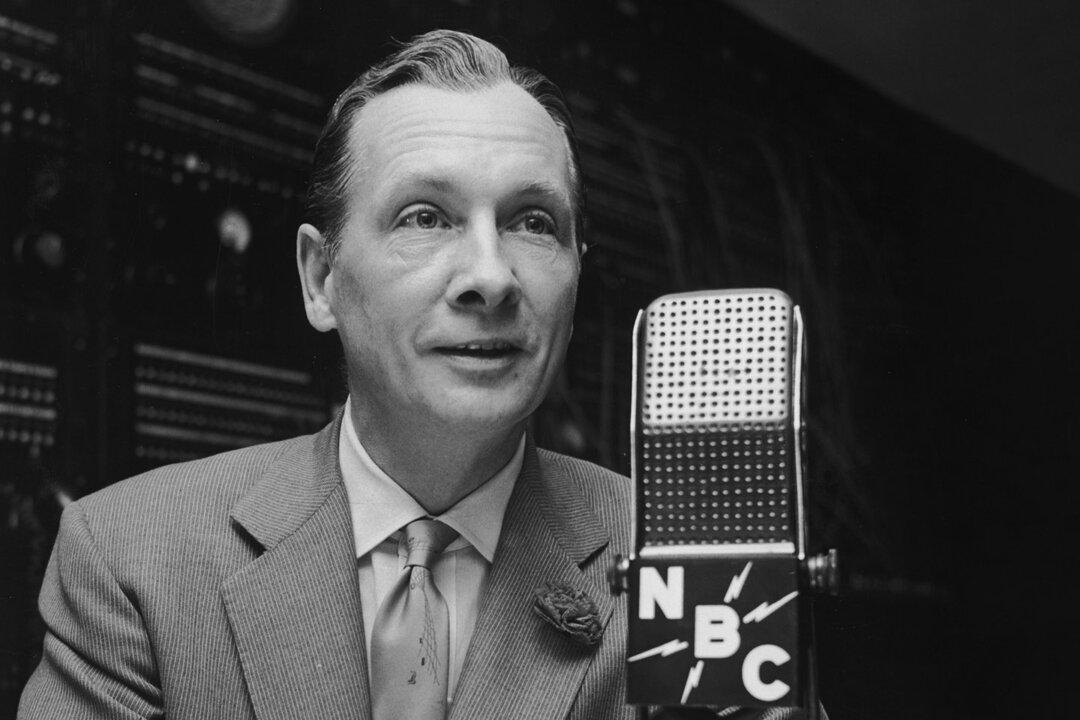

With the country basking in change, Sylvester L. “Pat” Weaver Jr. sought to shake up mass communications with some fresh ideas both in radio and the fast-growing world of television, the newest source of daily entertainment and information.