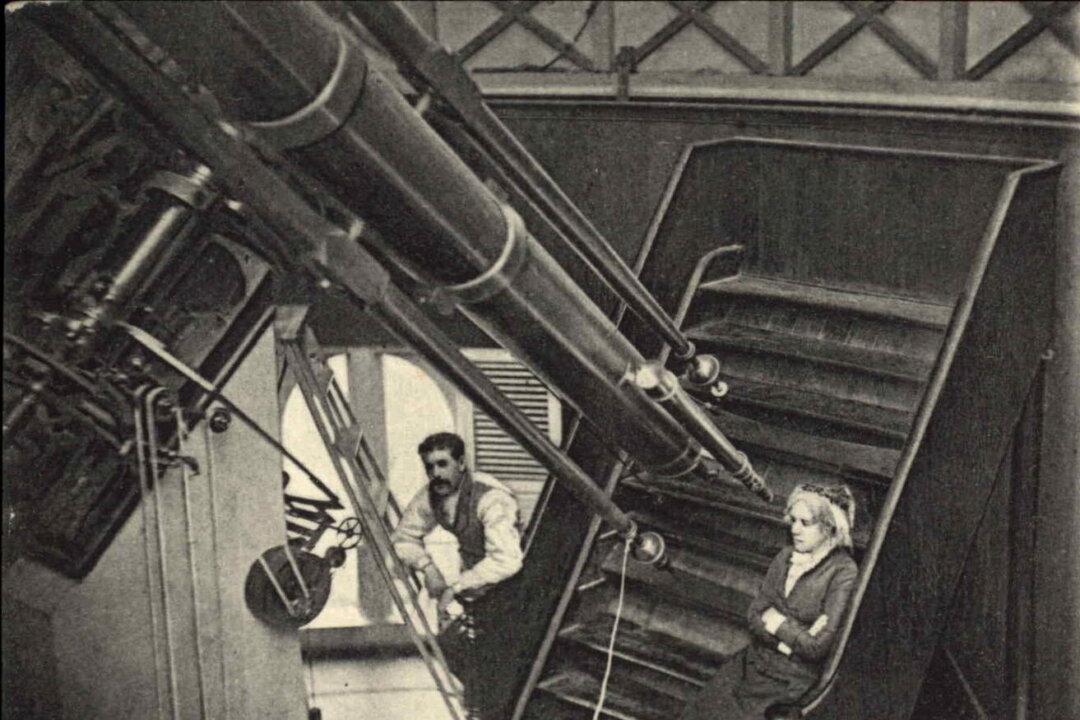

Maria Mitchell grew up with a passion for astronomy, something she received from her father. Her gift for astronomy and mathematics provided her careers in both astronomy and navigation. This dedication to the field of astronomy would literally leave her name among the stars.

A Brilliant Student

When John Augustus Roebling immigrated in 1831 from Prussia to the farming commune in Saxonburg, Pennsylvania, he quickly found that he was no farmer. Bridges were more to his liking, and he soon became one of America’s most prominent and innovative bridge builders.Maria Mitchell (1818–1889) grew up on the island of Nantucket in Massachusetts, the daughter of William and Lydia Mitchell, and one of 10 siblings. Raised in a Quaker household, she was provided an education with her brothers and the local boys. It also helped that her father was a teacher. Her father, an amateur astronomer with a passion for studying the stars, left a lasting impression on Mitchell.