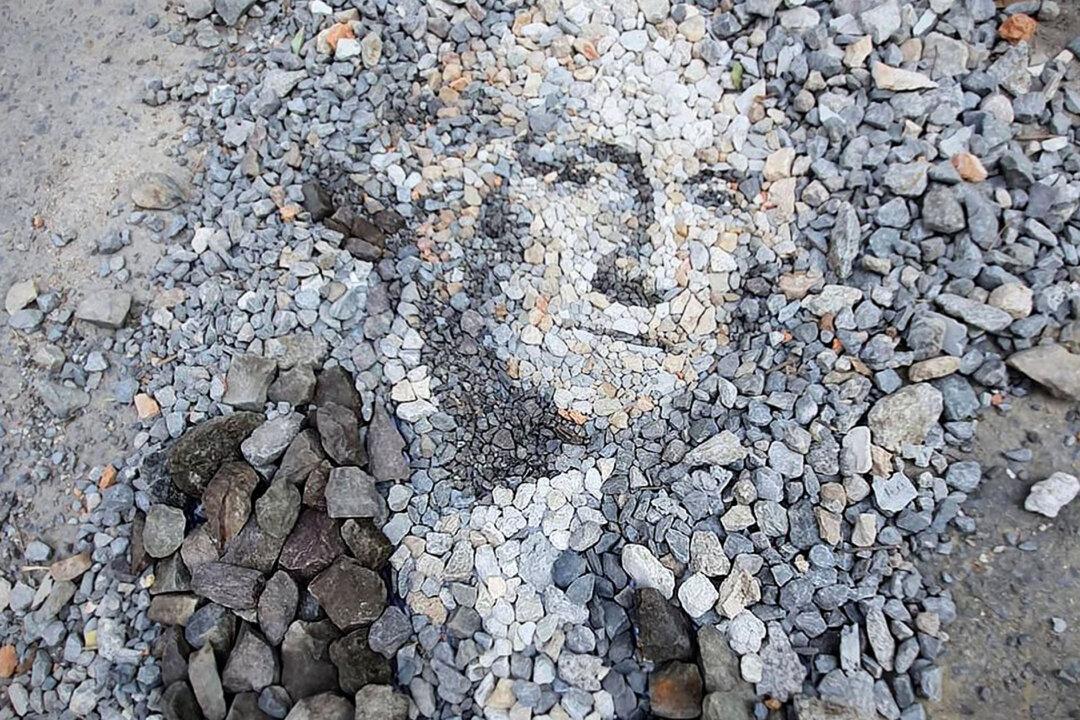

Inspired by esoteric Tibetan sand mandalas and their corporeal impermanence, one UK-born artist uses natural landscapes as his canvas, and paints with pebbles of various colors, shapes, and tones to portray earthwork likenesses of Michelangelo’s David and Mark Zuckerberg—a challenging juxtaposition to be sure, but incredible to behold and no less beautiful.

That artist, 45-year-old Justin Bateman, now based in Chiang Mai, Thailand, believes that artwork should connect with our natural environment, and draws inspiration from land art sculptor Andy Goldsworthy and Philip Guston, who challenged the notion of “high art.” And so, Bateman set off into the forests, jungles, and beaches of Thailand and Indonesia to create his colorful, mosaic-like masterpieces.