VARNA, Bulgaria—As a young man, Professor Ivan Barzakov tried to escape from Bulgaria’s communist regime. Born in Sofia, he pursued studies in English and Bulgarian philology.

He eventually emigrated to the United States and now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Barzakov developed an innovative method, which accelerates learning and allows a deep perception of the arts. Known as “AOLIA,” the method is taught at Educational Institute International, which he established in San Francisco.

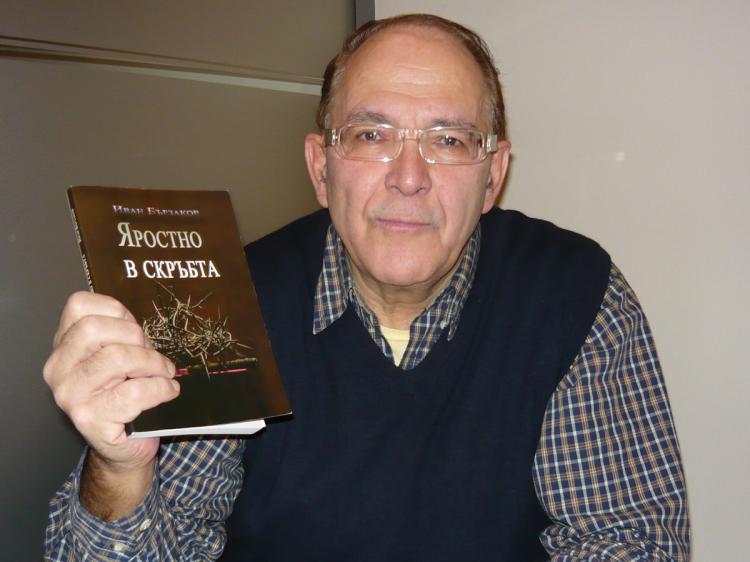

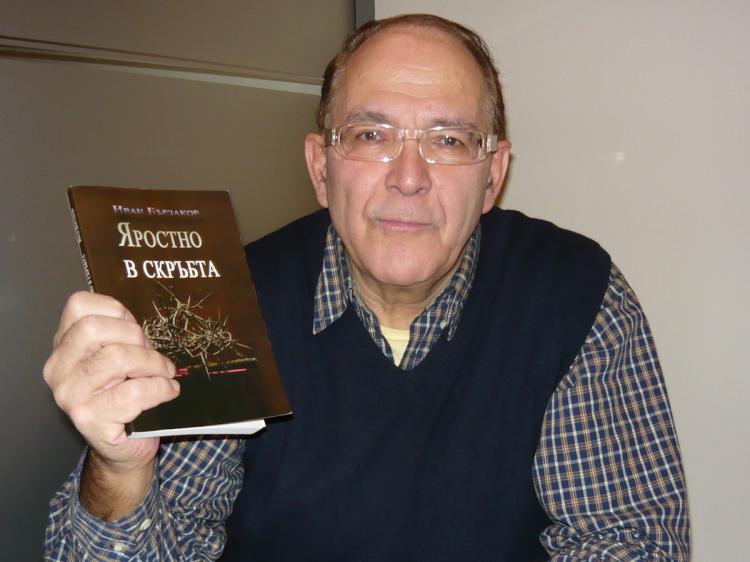

His first book of poetry, “Raging in Grief,” was recently published in Bulgarian. At his book launch in Varna, Professor Barzakov spoke with The Epoch Times.

The Epoch Times (ET): Professor Barzakov, tell us about your two attempts to escape from Bulgaria during the communist era.

Barzakov: The first time I was 19 years old. I made it into Turkey. About 18 miles past the Turkish border, I became ill and decided to return. They [Bulgarian police] arrested me outside the border.

I was beaten while in custody and moved around to different police stations. However, I was never charged with trying to escape. My second time, in 1976, was successful. I [finally] ended up in America, but it was not as easy or fast as people might think.

ET: Why did you go to America? You reached Italy and you could have stayed in any European country.

Barzakov: At that time I crossed the border into the former Yugoslavia and from there headed straight to Italy. The story of my flight is quite interesting. Traveling through Yugoslavia, I slept in Ljubljana and then I went by bus to the Italian border.

I planned everything in advance. I had to swim more than three miles in the Adriatic Sea to reach the Italian coast. It was September 10, 1976. I carried a bag of Vaseline for the swim.

I naively thought that if someone caught me, since there was sanatorium for rheumatic patients nearby, I would say that I was from the sanatorium and this was my ointment. This wouldn’t work, of course, but I thought I should give some explanation. Thank God, it did not get to that point.

When I found a place to get into the Adriatic Sea, a storm broke. I swam for a long time in the stormy sea and finally figured that I had swum further than I had planned. When I came ashore, I saw that I was still in Yugoslavia, near the [Italian] border. I dashed inland almost naked. An armed Italian frontier guard met me and I thought this would be the end of everything.

But little did I know. The first night I slept behind bars while my identity was checked; after all, I had no documents. Then I was taken to an Italian refugee camp where one can get temporary immigration status.

I could not stay in Italy or go to another European country since one needed a family there and I did not. As a political refugee I had to choose Canada, Australia, or the United States. I chose America. I knew that it would be the hardest there, but the best. So I did. In the United States I was able to realize the ideas I had.

ET: How did you accomplish your ideas? Did you need some help?

Barzakov: No one helped me. At first I began to study in New York. I won a scholarship. Later on I was invited to teach in San Francisco, California. After my studies, a group of scientists and I founded an institute of learning. My first lectures were in Canada, where I began to develop the innovative method for accelerated learning and a deep perception of the arts, which I named “Aolia.”

America always attracted me as a country of asylum. This is a country of opportunities. There is no discrimination. If one works hard and has an opportunity, one can succeed faster than anywhere else. As the developer of the system, who lectures, and conducts seminars worldwide, I was invited to speak at one of the most prestigious clubs in San Francisco.

ET: You visit Bulgaria often. What do you think about the country 20 years after the rejection of communism?

Barzakov: Yes, I am very often in Bulgaria. With the publication of my poetry book, I have been able to visit many cities. However, in Varna I was welcomed by the greatest number of people.

One of the visitors at my book launch used the following expression which most accurately describes the current situation [in Bulgaria]: “There’s no change, but manipulation,” meaning there is no real change but things are manipulated to look different when they are really still the same.

I feel a great desperation in people. There were and there will continue to be difficulties. It was the same in the Czech Republic and Hungary. But in Bulgaria I see something else: confusion.

Now with the recently elected government, perhaps there is hope that something will change. But so far I have only seen a complete disappointment.

The system is totally changed, but the structures are maintained. Some who were in power during the communist era are back in power, backed by their black money.

Differently than before, people can now speak freely in newspapers and on television. But now the slavery is economic and not political.

My book is called “Raging in Grief” because of the fury that I feel when I see young people doing drugs and becoming morally corrupt. I see all the sorrow and despair in people, and do not want to put up with it.

ET: Why do you think the despair exists? Has the thinking of people, burdened by years of communism, changed?

Barzakov: The reasons are several. Germany, for example, was totally destroyed after the Second World War. Literally everything was destroyed. With a little bit of help and lots of effort West Germany recovered within a very short period. It rose like the Phoenix.

In the Czech Republic it was the same as well, as in other former communist countries in Europe.

Bulgaria now ranks last in the European Union, while a few years ago it was sixth. There is no decent explanation. How would people not get desperate?

ET: Do I understand that Bulgarians have not yet cleared their mind of its communist past?

Barzakov: You could say so.

They ask me what the answer for Bulgaria is. I am not a politician and I cannot say, but I know the role of the writer, the playwright, the director. It is to understand and to write the whole truth about things, about the grief.

That’s why the title of the book I presented is as such. It’s not a matter of melancholy, but about the fury of poets, what artists need to have.

In the past, it was a nightmare in Bulgaria. There was continuous recruitment to fill the ranks of the regime and as informants. This is a great offense to the Bulgarian nation and every individual. This is slavery.

ET: For many years you have lived and worked abroad. How do you see the situation now in Bulgaria? Did Bulgarians realize and understand what they lived in, and can they transcend their old thinking?

Barzakov: Unfortunately, very little. There is now some change, especially in the young who ask [the older generation], “How could you have tolerated it?”

But look at the facts. Parents do not tell anything to their children, and the textbooks do not write anything about it. There has been silence for 20 years.

Now that some children are adults they realize that their father was arrested and imprisoned and their mother was politically persecuted. This fear, this reluctance to talk about the past, has penetrated very deeply. It is like cancerous tissue, which must be cut out furiously.

We must awaken from this lethargy. Apparently 20 years are not enough. More willpower and optimism is needed.

And here is the role of artists. They need to ignite public opinion. In Bulgaria, things must change. There must be law and order. But if people are poor, it is hard to demand respect for the law.

We should read more poetry and live with it. When one starts to value what feeds the soul, many things will change.

Read the original Bulgarian article.