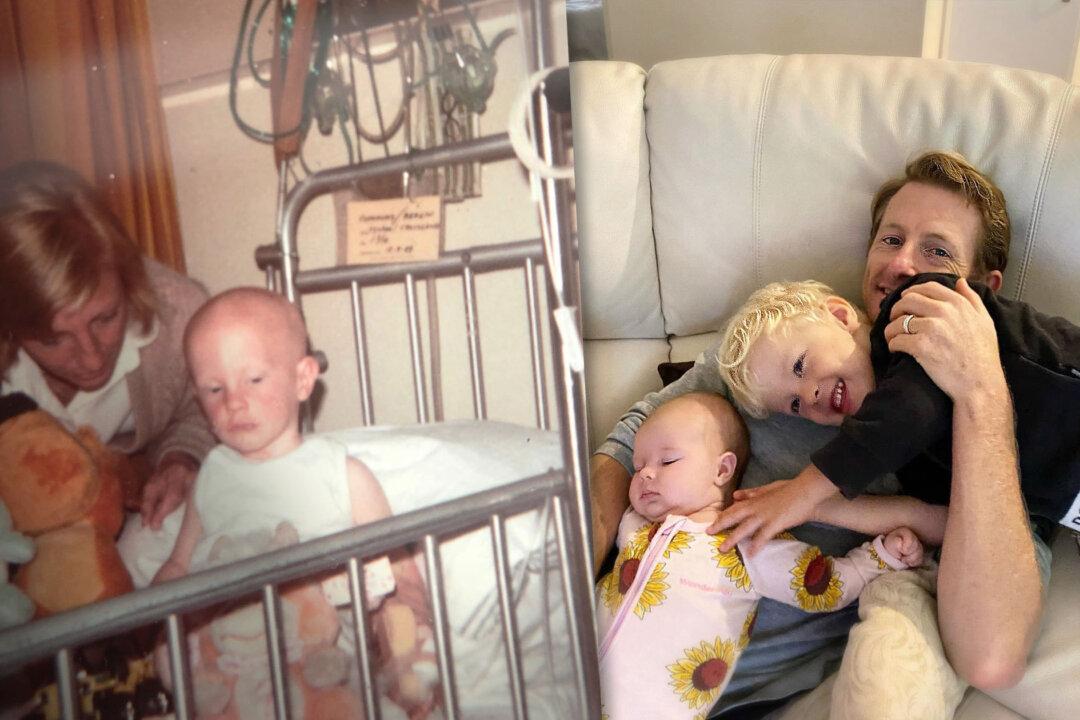

“I started chemotherapy on May 2, 1985,” said Michael Crossland, 38, who was diagnosed with cancer at just 11 months of age.

The doctors at Coffs Harbour Hospital touched his stomach and said, “Whoa, what’s going on here?” They scanned him, and Crossland was sent off to a Sydney Hospital for immediate treatment to save his life.