There are a few key pieces of grammatical knowledge that can make an immediate difference to the quality of children’s reading and writing. In this column I look at verbs, and suggest four actions that would improve literacy outcomes.

What Do You Know About Verbs?

When asked, most people say a verb is a ‘doing’ word, which means most people don’t know much about verbs. Thinking that verbs are ‘doing’ words is why 80% of my preservice teachers struggle to find the verb in the sentence ‘I am afraid’. (The verb is ‘am’)

Thinking a verb is just one word is why 80% of my preservice teachers can’t identify the verb in the sentence ‘I’ve seen every Tigers game this year.’ (The verb is ‘have seen’)

When we think of verbs simply as ‘doing’ words, our most common verbs slip under our radar - like am, is, are, were, was, been, have, had.

These verbs not only work on their own in sentences e.g. ‘I am a teacher’, but they work together with other verbs to form chains. Those verb chains tell us what’s happening in the sentence but also when it’s happening.

For example, in the sentence ‘I have been teaching for 20 years’, the verb is ‘have been teaching’. This verb chain tells us what is happening - ‘teaching’. But it also tells us when it has happened. The ‘have’ tells us that I still teach, ‘been’ tells us that I taught in the past, and the ‘ing’ on the end of teaching tells us that I have continuously been a teacher from the past to now.

Changing our verbs to indicate time is what we call ‘tense’ - and depending upon who your favourite grammarian is, we have around 12 different tenses in English.

That means we can organise each of our verbs in 12 different ways to give different time nuances. For example, here are some ways we can change the verb ‘to teach’.

I taught for 20 years, I was teaching for 20 years, I have taught for 20 years, I had been teaching for 20 years, I have been teaching for 20 years. Each has a finely nuanced difference - but a meaningful difference that can muddle comprehension if you don’t get it right.

Action 1 - stop telling kids that verbs are ‘doing’ words, they can also be about being, saying, thinking, relating. They tell us what’s happening, but they also tell us when it’s happening. And they are not always just one word.

Who Cares?

When you are a native speaker of English this information about the language is often surprising - we rarely recognise how complex our language system is when it comes to us so naturally. In fact, it is so intuitive to most of us that we wonder why we need to know this stuff. I mean, really - who cares? How does it make me a better teacher or, indeed, a better reader and writer?

These English language structures don’t come naturally to all our students - and it is no coincidence that the students for whom this is not innate knowledge are the same students who make up the long underachieving tail in our schools. They speak English as an additional language or dialect, or they just don’t speak ‘school English’. In our most disadvantaged schools, that can be 100% of the school population.

The way verbs work in English is particular to English. And if school English is not the language of your home, then you really need someone to show you how it all works. It is why we need specialist English language teachers in our classrooms - but instead governments are removing them.

The student who writes ‘I seen that movie’, is making the same error as the student who says ‘they done their homework’, or claims ‘I been learning guitar for 3 years’. They are taking a structure from their everyday spoken language and using it in their school writing. And teachers put red lines through it.

If we think this language is important enough to mark with red crosses, then surely we must think it is important enough to teach. ‘Done’, ’seen’, ‘been’, ‘gone’ are what we call past participles, and that means in formal ‘school English’ they don’t work by themselves - they join with ‘have’, ‘had’ and ‘has’ to tell us about something that we have done in the past.

Action 2 - explain errors, let kids in on your ‘insider’ knowledge

It’s Not Just About Remediation, It’s About Extending

When teachers read flat and boring story writing, they tend to think it is about the adjectives, or lack thereof. But it is so often about the verbs. Static verbs make static writing. Choosing verbs thoughtfully can turn static pictures into movies.

Action 3 - analyse the verbs in your children’s story writing. Are there a variety? Are they stuck on the ‘being’ verbs of am, is, are, was, were or is which can produce a static picture, or is their repertoire limited to the verbs that predominate in spoken language, like went, did, had, said, which fail to get their stories moving in dynamic ways?

The Teaching Should Be Fun, and for Everyone

The best way to teach about verbs is by looking at how authors use them to make their stories spring to life, and the best way to do that is through drama.

Role-playing and acting out the stories we read - and the stories we write - helps us pay attention to verbs in writing and how they work, because verbs so often tell us how the character moved, the way they spoke, how they feel and the nature of the interaction between characters.

This language work should be for all children in every year of school. It builds a love and fascination for the language - and helps children use language in powerful and purposeful ways.

Sadly, the children who need this work the most are the ones who are sent off to do meaningless stencils of out-of-context sound and word work.

Action 4 - be dramatic, creative and enthusiastic when you teach language. There is nothing boring about grammar; it’s bad teaching that’s boring.

Misty Adoniou does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

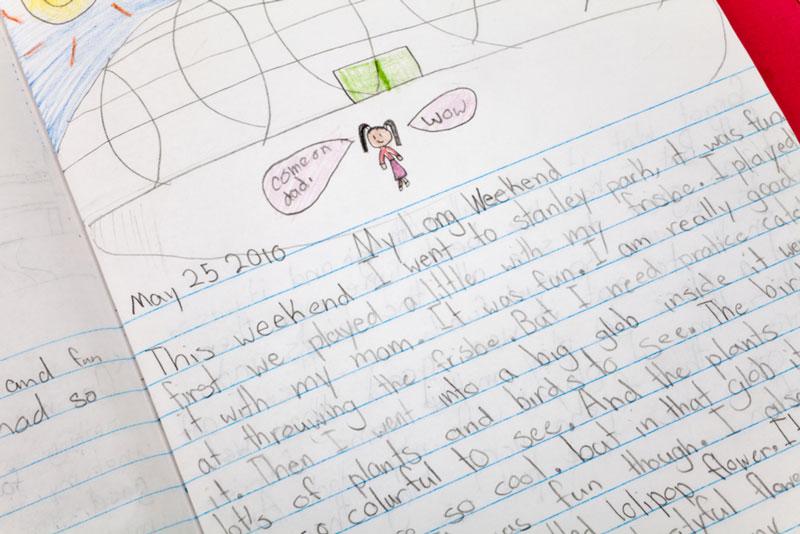

*Image of “child writing“ via Shutterstock