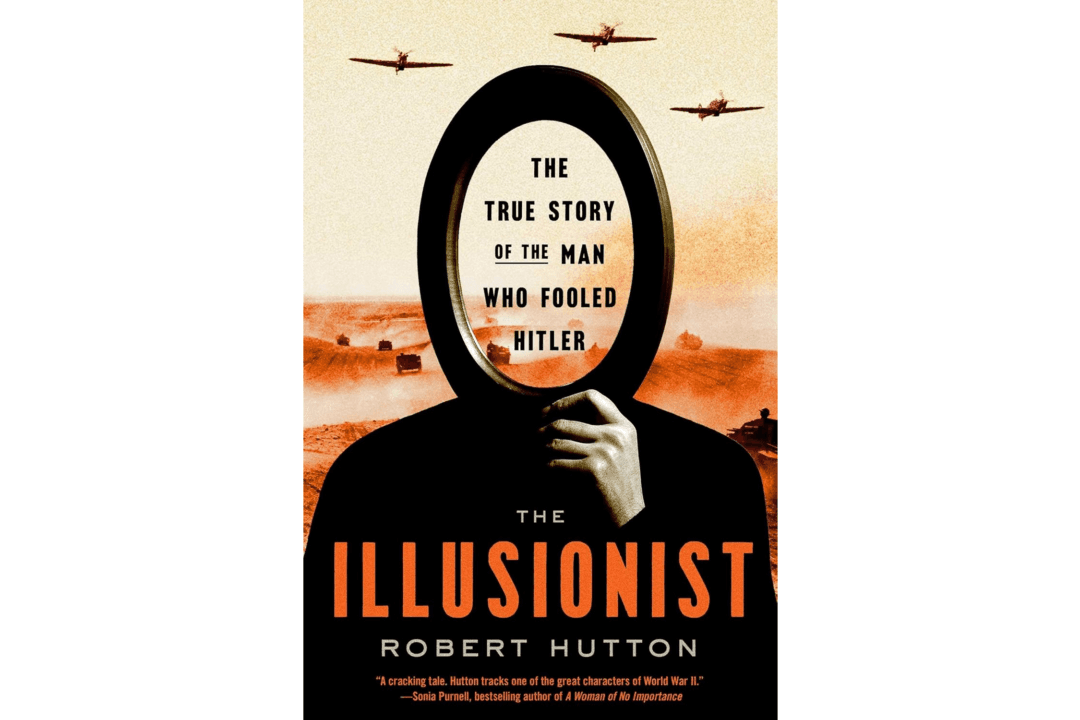

It may be impossible to win a war without firing a shot, but there are moments in war that an enemy can be defeated through such impossible methods. As Sun Tzu once noted, “All warfare is based on deception.” Deception is precisely how enemies can be defeated without bloodshed, and Robert Hutton makes this abundantly clear in his latest book “The Illusionist: The True Story of the Man Who Fooled Hitler.”

As tends to be the case with World War II, there’s always another interesting person to write about. Col. Dudley Clarke, a member of British Intelligence during the war, is one such person. Unsung heroes from this war come to the surface because either they’ve hidden their stories until late in life or their stories are hidden for reasons of national secrecy. Clarke happens to be in the latter camp.