In a world dominated by texts and emails, schools are devoting less attention to handwriting. But experts warn that the trend deprives students of a valuable skill.

In her 2009 book “Script & Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwriting,” Kitty Burns Florey recalled the 1950s at St. John the Baptist Academy in Syracuse, New York, where she progressed from pencil, to ink well, to the newfangled extravagance of ball point pen. Her exploration with penmanship cultivated a sense of identity not possible with a keyboard.

“It’s obvious now that most of my scriptorial attempts were outrageously pretentious, appallingly twee, but I considered each one the height of cool—the proper handwriting for an aspiring Bohemian, a future writer, a deeply sensitive person who wrote deeply sensitive poetry and then burned it in the sink, weeping,” Florey wrote.

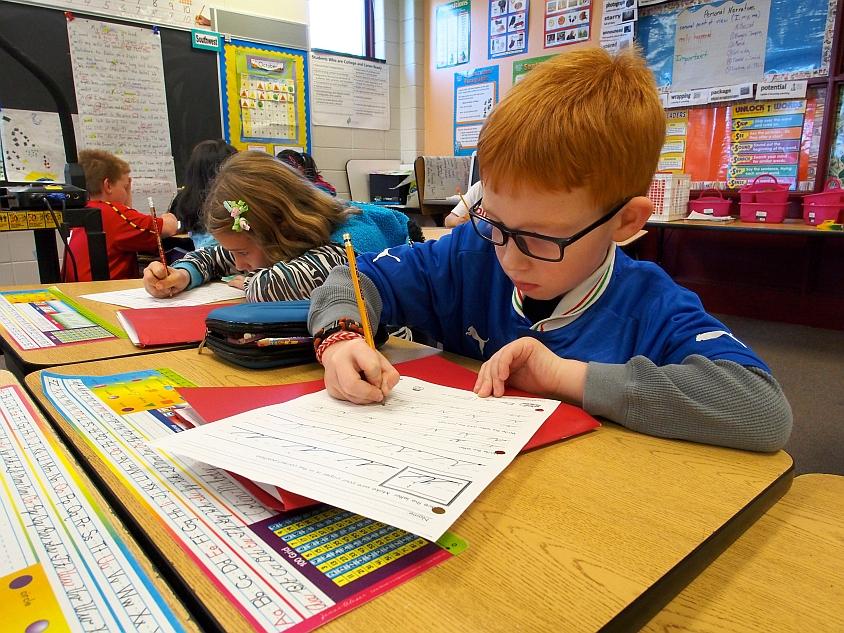

In today’s classroom, however, students have little time to learn the basics, much less experiment with personal style. The latest federal standards under the Common Core only cover handwriting in kindergarten and first grade.

States have the option to expand handwriting instruction, but many don’t think kids need much more. Today 41 states don’t require cursive, and most districts choose to reserve class time for other skills.

“It’s much more likely that keyboarding will help students succeed in careers and in school than it is that cursive will,” said Morgan Polikoff, an assistant professor of K-12 policy and leadership at the University of Southern California.

Penmanship and the Cognitive Process

People who value penmanship point to recent studies which show a strong connection between handwriting and brain development. Research showed that the act of writing helped children learn letters and shapes, develop fine motor skills, and generate better ideas than when working on a computer.

MRI evidence from a 2010 Indiana University study showed that children demonstrated much more neural activity with handwriting practice than from just looking at letters on a page. A 2012 study suggested that writing by hand contributed to children’s ability to process letters and build reading skills in ways that typing could not.

“I think many educators are truly unaware exactly how children learn, how their cognitive process works, and how writing by hand impacts on that cognitive process. The recent research has to filter down to the educators who are responsible for curricula,” said handwriting expert Nan Jay Barchowsky.

A Running Hand

Barchowsky and Florey want schools to realize the importance of handwriting, but they also believe the old methods waste time and discourage practice. In schools that teach cursive, for example, experts see most kids reverting back to the print script that they first learned. As a result, many adults wind up with chicken scratch.

“Most schools for the last 75 years have been teaching a print script and then they add on the cursive. When they did this they caused a lot of problems in my view. Because I think it’s important that kids learn one way to write and not mess it up by teaching two different sets of motor memory,” said Barchowsky.

The word cursive conjures a specific style of loops, swoops, and a rather curious capital Q, but the name actually refers to a sense of flow—a running hand.

Some form of quick script has been around almost forever. Not just in the Roman alphabet, but the Phoenicians, ancient Egyptians, and other cultures all developed a writing style that allowed for more speed and facility than standard notation.

With much of class time spent writing things down, today’s students still require a script that is quick, comfortable, and if they wish to communicate effectively, legible too.

Enter Italic

Barchowsky and Florey advocate for a handwriting style known as italic. Although it bears the same name as the slanted typeface, italic handwriting is like a hybrid between print and conventional cursive. A product of the Italian Renaissance, italic letters resemble print, but their flourishes allow for greater flow.

According to Florey in her September 2013 editorial “Does Handwriting Still Matter in the Digital World,” children easily take to italic because it requires fewer strokes. It’s easier to write, but also easier to read, and has been adopted in schools throughout Europe and Australia.

“We may not turn to handwriting every day (though I'll bet most people do), but we use it often enough that it should be always, as it were, at our fingertips: fast, reliable, legible. And yet I have no doubt that 90 percent of the people reading this article have absolutely dreadful handwriting,” she wrote.

According to Barchowsky, handwriting is deeply personal. “It is how you present yourself to the world. It has to do with your hairstyle, the clothes you choose to wear,” she said.

Barchowsky adds that the sense of identity associated with handwriting may also be why schools are so resistant to change.

“I think it stems from handwriting being a very egocentric skill. I think that plays into an emotional attitude toward handwriting, and a ‘that’s the way we always did it’ kind of a thing,” she said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.