Author foresees a new China after the Olympics

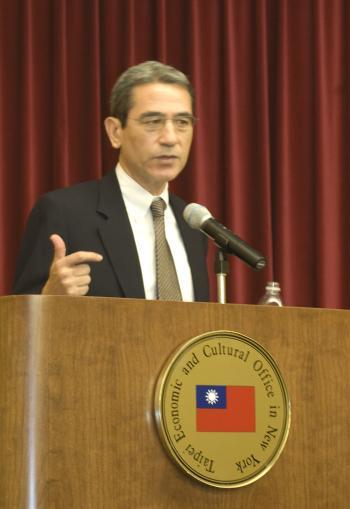

NEW YORK—Gordon Chang has written several books on China. The writer recently spoke at the Taipei Cultural Center in New York where he discussed what will happen in China after the Beijing Olympics.

NEW YORK—Gordon Chang has written several books on China. The writer recently spoke at the Taipei Cultural Center in New York where he discussed what will happen in China after the Beijing Olympics.