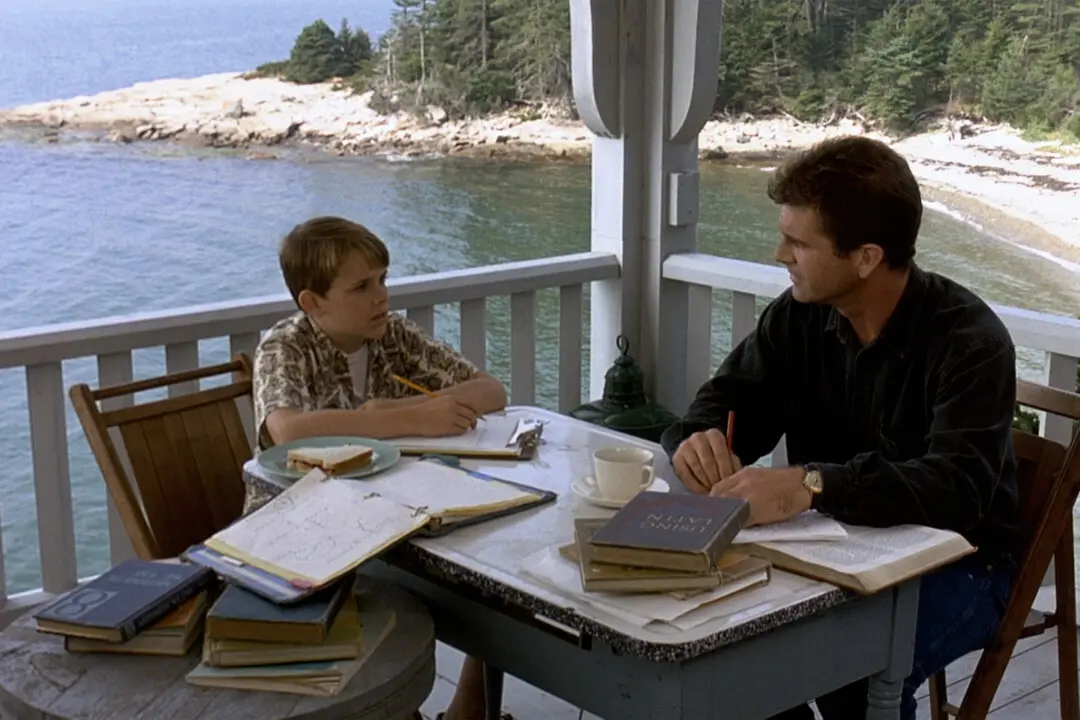

NR | 1 h 58 min | Drama | 1947

Finley Peter Dunne, a 19th-century American humorist, once wrote that journalism must “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” Jewish writer and one-time journalist Laura Zametkin Hobson honored that spirit in her novel “Gentleman’s Agreement.” It’s about a crusading journalist who challenges anti-Semitism.