Europe’s long fascination with ancient Chinese art and culture isn’t new, as it was even mythologized in the Middle Ages. However, it was during the reign of Louis XIV that a new era began, bringing the East and West closer than ever before.

“Most high, most Excellent, most Puissant, and most Magnanimous Prince, Our Dearly Beloved Good Friend, may God increase your Grandeur with a happy end. Being inform’d, that Your Majesty, was desirous to have near your Person, and in your Dominions, a considerable number of Learned Men, very much vers’d in the European Sciences, we resolv’d some Years ago, to send you six Learn’d Mathematicians Our Subjects, to show Your Majesty what ever is most curious in Sciences, and especially the Astronomical Observations of the Famous Academy we have establish’d in our good City of Paris. ... Your most Dear, and Good Friend, Louis.”

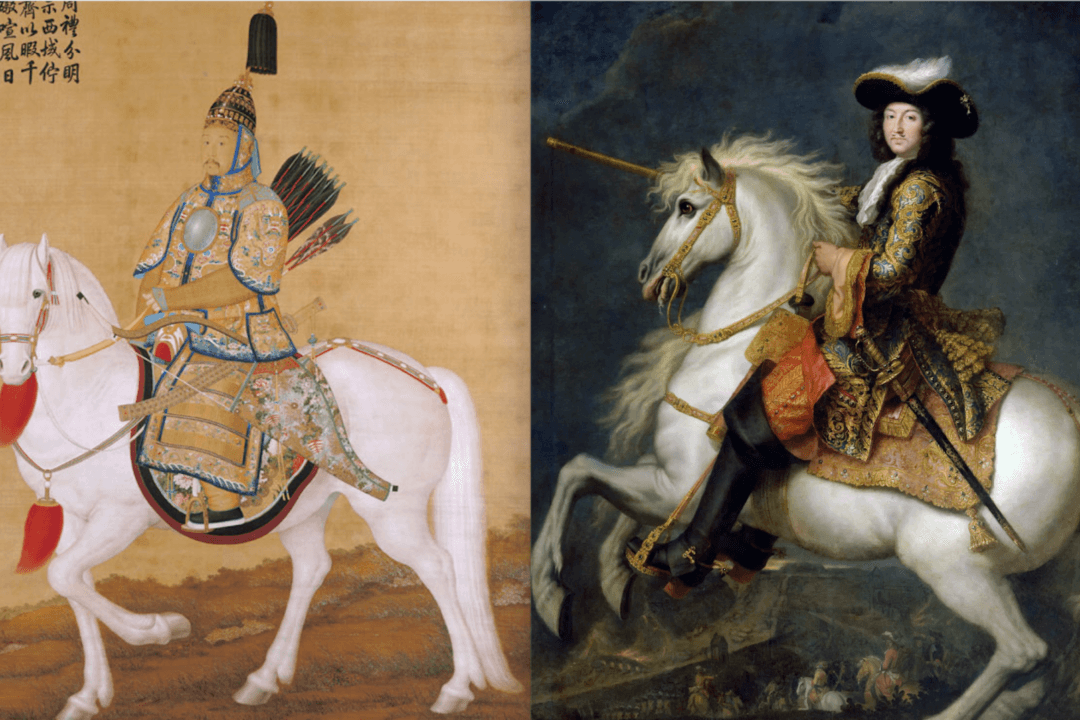

These two monarchs at the eastern and western ends of the Eurasian land mass stand out in the world of the late 17th century. In the West, Louis XIV (1638–1715) ruled France for 72 years as a member of the Bourbon dynasty and was the longest reigning European monarch. In the East, Kangxi (1654–1722) ruled China for nearly 62 years as a member of the Qing Dynasty and the longest reigning Chinese emperor. Both of them loved riding, hunting, and archery, were fond of the arts, and ushered in a golden age during their reigns. They are unique, yet they present with striking similarities.