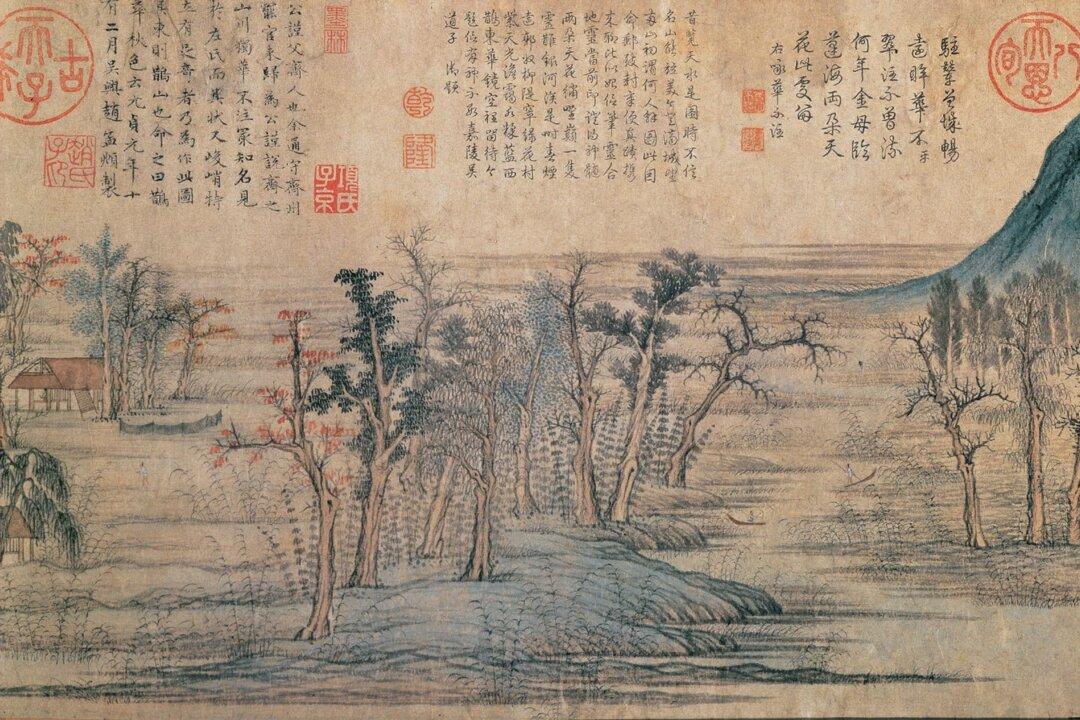

Chinese landscape painting, known as shan shui (“mountain water”), can be considered one of the highest forms of expression in ancient Chinese art. But what makes this genre so unequivocally identifiable?

It begins with the fact that the ancient Chinese believed that heaven and earth exist together in harmony. Thus, ancient Chinese landscape artists sought to portray nature’s relationship with the entire cosmos.