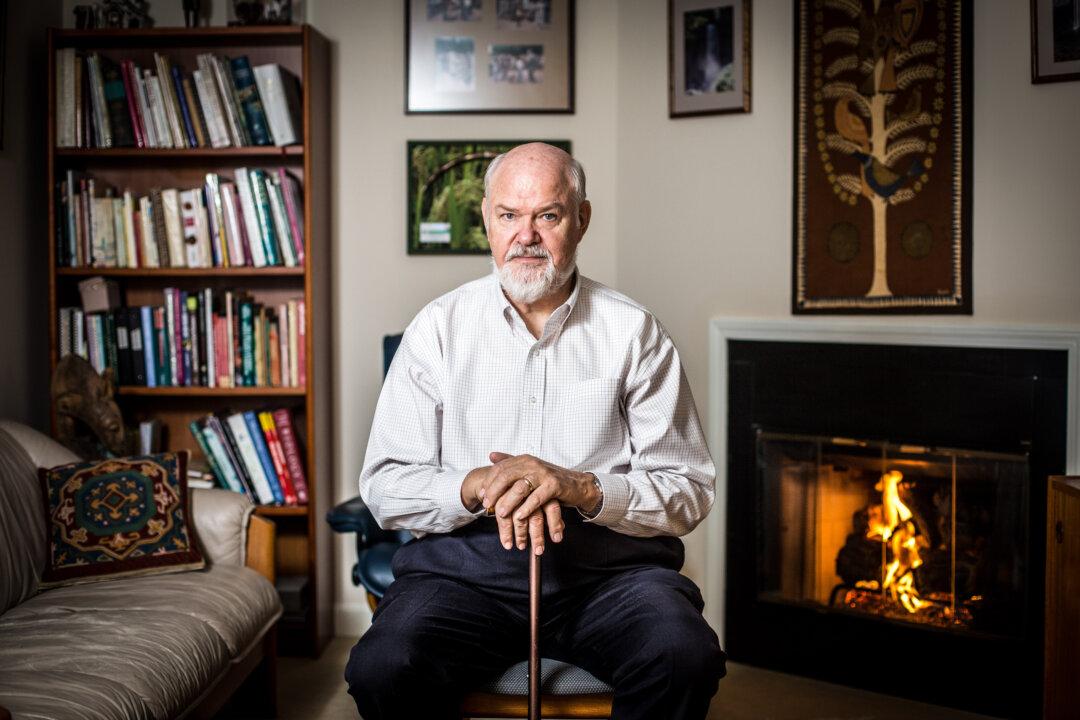

Tim McGreevy of Pickleflat Farm eats flash-frozen chickpeas with his morning smoothie. He marvels with excitement after learning that leftover bean cooking water can be used to make chocolate mousse. He spends his days either tending his crops and small herd of Angus grass-fed cows, or advocating for his favorite subject—or both.

McGreevy grows dry peas, chickpeas, and lentils, in rotation with wheat and barley, on 60 acres of richly fertile rolling hills located just off McGreevy Road, in the heart of eastern Washington’s Palouse Country pulse-growing region.

Pulses are the dried beans, peas, lentils, and chickpeas that historically have only made their presence known for most of us in hearty soups and stews. But times are changing for the inconspicuous pulses, as right now they are the subject of a massive global marketing push to prove their potential.

“I am really into these products,” said McGreevy, who has been a spokesperson for pulse crops for 22 years, as CEO of the USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council, and as head of the newly formed American Pulse Association, during a recent telephone interview.

McGreevy says he counts himself lucky to be working with pulses. “I am off to save the world,” he tells his wife each morning when he leaves for work.