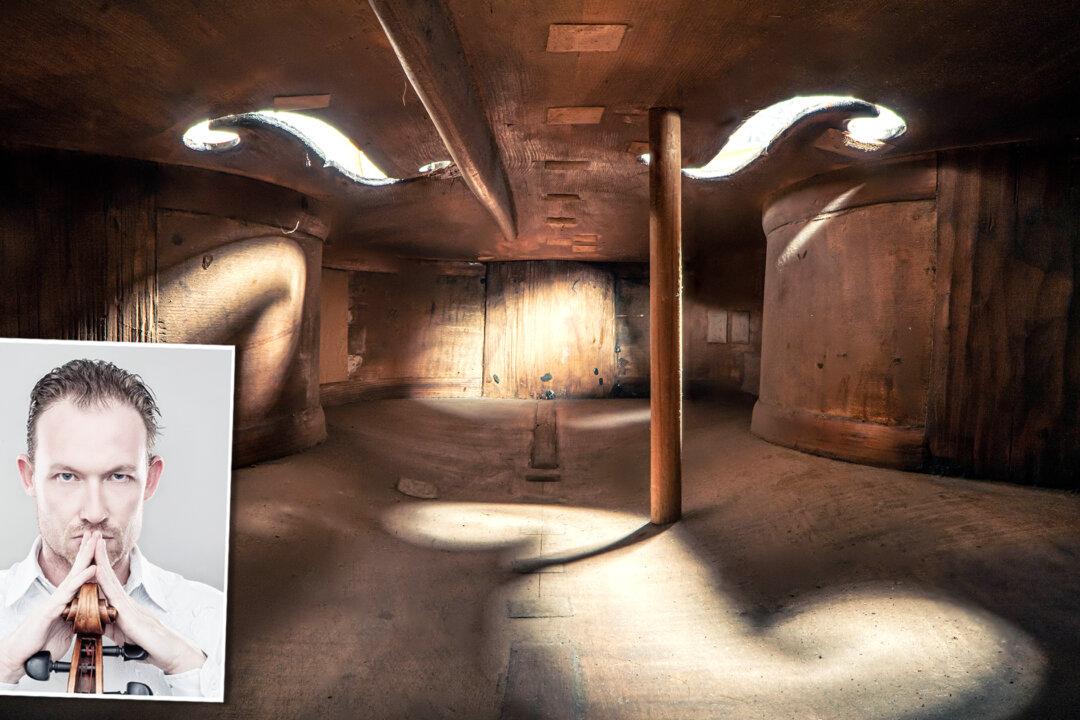

A former concert cellist returned to a long-time love of photography during the pandemic, using new camera lens technology to explore musical instruments like never before. His compelling photos of instruments’ interiors are at once close-up and labyrinthine, giving us a peek into a world of vast, secret spaces.

Charles Brooks, 43, has been a musician most of his life, performing as principal cellist with orchestras in Brazil, Chile, and China. A little burned out from the pressured lifestyle, he returned home to Auckland, New Zealand, in 2016 and took up photography full time.