The interview was conducted as a result of the upcoming March performances by Divine Performing Arts at Berlin’s Friedrichstadtpalast.

Epoch Times (ET): Mr. Puttke, what professional experiences do you have you related to Chinese dance?

Martin Puttke (MP): Competitions permitted me to closely follow Chinese ballet. Since the 1980s a virtual boom has existed, a positive development as to aesthetics and dance techniques. That extends to the broadening of the dancers’ artistic repertoire, into modern presentations, all based on a solid foundation. Quite astonishing.

During the 50s and 60s, Chinese ballet still adhered to Soviet style. Many recognized, well-known Soviet ballet masters had worked in China and established somewhat of a foundation. But then, according to my estimation, a rift occurred—during the 70s and 80s, when China had opened the dance door a crack, a positive development. One example was the American choreographer Ben Stevenson. This is as much as I would say about Chinese ballet.

ET: Are you speaking of Chinese ballet?

MP: I am only discussing Chinese ballet here; I have a positive impression!

ET: Have you followed the development of Chinese ballet for the past 20 years? As you know, much has changed in China. How do you see the dance now?

MP: When I was named ballet director in Essen, I had to decline many invitations abroad, because the work at home kept me tied down. Once I do something, I do it at 100 percent. My impressions of Chinese dance during the last ten or twenty years is no longer as complete as during the time before. I regret this, because it interests me greatly.

How far has Chinese ballet come? What is happening in ballet training? What model does Chinese ballet training follow? Is it the best classical training that incorporates timely, modern dance? Those are not merely problems of demands on the dancers and on choreography, but primarily the dancers’ first-class training. That means dancers must be educated and trained well enough to perform not only classical numbers, but these people must also be open enough—mentally and physically, to master modern dance repertoire.

ET: In your view, what are crucial points during ballet training?

MP: I emphasize the modern dancers’ unity of mental and physical excellence. That presents a problem for me, because often instructors merely stress the physical aspect of training.

ET: That is an interesting, important point. You took part in the opening of the three-part showing of “Political Body.” There was supposed to be dialogue between you and Miss Plisetskaya.

MP: Correct.

ET: Could we discuss the “Political Body” exhibit, an interesting, not often seen interconnection between politics and dance? Many performers have the attitude, “we are dancers,” or “we are sports people,” and they concentrate on physical aspects and believe they have nothing to do with politics. Could you give us an insight into the purpose of such an exhibit and how to disseminate such information worldwide?

MP: I find the title exceptional, because it appears to separate dance from the political realm, and yet is quite specific that political intent among people, though often not obvious, is always present. Even non-political action makes it political. A person per se is a political entity—no matter whether the dance isn’t, it does not matter.

ET: How do you define politics?

MP: Politics is a public matter—everything we do is a political matter, because we live among people in society. Were I to live alone on an island, like Robinson Crusoe, I would answer your question differently.

ET: We are no Robinson Crusoe’s.

MP: Since we live among political and social constraints, the body automatically becomes a political representation—those who appear on a stage and confront an audience, even though the performer believes to not represent a political comment, by their sheer appearance, the dancer/actor performing before the public, becomes a “body politic.”

ET: Even though he does not mean to make a political statement through the dance?

MP: Yes, even during dancing La Sylphide a political interaction takes place. How? By presenting a work from the Romantic era on stage within the framework of a cultural event. That takes on a cultural/political meaning. It has become the custom to indoctrinate dancers that their art can be representative of events in human life, represented in other art forms through writing, drama, film, or the media. And they think these are non-political. But that is erroneous when pondering what constitutes a political entity. Even people’s emotions eventually become political expressions. When someone expresses despondency or the feeling of love, I see those as the emotions of a political being: man is a political being. And for the exhibit—one cannot consider Maya Plisetskaya anything but a political entity, because her past is inseparable from the intimate connection with her art—in her case it is dance, always colored with politics.

ET: Not merely her father’s murder during the time of Stalin’s cleansing, but you also refer to the years she lived in the Soviet Union?

MP: Surely, personal problems play a huge role. Her father was murdered; her mother was exiled; Maya was practically an orphan whose relatives took her in. Her uncle, her father’s only brother, was a member of Kennedy’s closest advisers. Now imagine her uncle being legal adviser to Kennedy’s team of advisers. Her father murdered, and her uncle an adviser to Kennedy! No wonder the KGB scrutinized Maya P. extensively. That made her a “body politic.” She was not a street dancer, but one of high caliber found once in a hundred years. That’s what made her a political entity, obviously. The KGB had to sanction and follow her every move. When she received invitations for guest appearances, it was not the ballet chief but the KGB or state chief who had to decide. Documentation exists that all Soviet State Officials had to deal with her—Chruchov, Gorbatchov, and Yeltsin.

ET: Until 1990, when she emigrated?

MP: Yes. That tells the whole of her political career. Her whole life revolved around disruption or lack of continuity—up, down, extremes bar none. The only continuity consisted of the term “No,” for anything she wanted to do, until the 1990 war. It was hugely important if she danced a classical role or voiced her desire to dance a piece that was choreographed by Maurice Béjart. Even though a choreographed piece may lack a political statement—for instance the bolero—it became a political statement. Her body was a highly political security “pamphlet!”

ET: (laughs)

MP: I have devoted 40 years of my life to international dance and had been engaged in the East as well as in the West. I never again met with a dancer’s career as heavily colored with political and artistic drama like hers. That is why prima ballerina Maya Plisetskaya enjoys an exceptional position and is a unique presence among all other prima ballerinas. None of the others—Galina Ulanova, Alicia Alonso, Margot Fonteyn—had as dramatic a career or life as Maya Plisetskaya. No one could have found a better representation for this exhibit.

ET: We have heard that a conversation between you and Maya influenced her a great deal...

MP: Yes, in the 1970s we spoke in her dressing room following rehearsal at the Bolshoi Ballet Theater. We pondered what role the dancer’s mindset influences the dance. Both of us concluded that the dancer’s stage performance is a clear indication of his or her dance craft’s intelligence or stupidity. We immediately came up with names—but of course we cannot reveal the names.

ET: Probably not; but how does one know the difference between an intelligent and stupid dancer?

MP: That is a decisive question. Observing Maya’s art on stage lets me conclude that the crux of convincing dance is not mastery of style or classic techniques, but simply a disciplined idea and mental comprehension of the dance’s expression. That alludes to representational intelligence—to distance myself from the physical perception, but to be able to portray a richness of feelings and ideas of someone else, a role, a part, through my body. That is a highly mental process, and not simply an exhibit of my own emotions. In Germany we call it “navel gazing.” You can actually raise this to a certain cultural level, but it is limited and limits the dancer. Maya Plisetskaya is exactly the opposite; I see her as a highly intelligent dancer. The conversation with her and the stage experience have never left me in my later career as a pedagogue.

ET: In what way have you pondered Chinese classical dance?

MP: Unfortunately, I have no access to Chinese dance. I spent some time in Cambodia and have observed their dancing. Basically, as a dancer, I am open to many expressions. I can only say that [Chinese dance] is impressive, but quite difficult for me to understand.

ET: Could this be because the gestures represent specific meanings?

MP: Yes, that too. That hides a highly interesting scientific question. The American psychologist, Sack, did a study on what the reason might be for Europeans to be much more open to European music than Chinese, Asiatic music. Hypotheses exist that postulate European music to be based on biological foundations. We react hormonally completely different to European music than to Asian music, and Asian people, again, react differently. If you translate that to dance, it becomes obvious that movements and harmony represented in European dance accord with a European’s body harmony. And vice versa, Asian dance culture accords with Asian body systems. But this kind of science is still in its infancy.

The connecting link [between Eastern and Western dance] is the Chinese dance culture’s representation of images, just like in the West. Classical European dance—due to its highly stylized technical structure and immense style-code has become far removed from pictorial interpretations, which might spell its death knell. I sense opportunities for connecting [to Asian dance]. Ballet must return to painting a picture and thereby raise the body’s interpretive ability. That is what Maya Plisetskaya does.

ET: Do you see a comparison between dance and calligraphy?

MP: Yes, absolutely! Dance represents whole-body calligraphy for me.

ET: Could you explain this a bit more?

MP: Yes—the mere movement of the physical body—there is not a millimeter, nor a second that does not have a meaning. And that brings us to calligraphy.

ET: Mr. Puttke, we thank you for the interview.

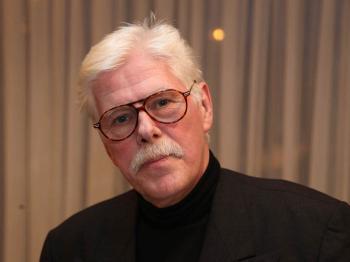

Martin Puttke is a dance teacher, and was a former director of the Aalto Ballet Theater in Essen, a German state, until 2008.

Maya Plisetskaya was Primaballerina Assoluta at the Moscow Bolschoi-Theater. Assoluta refers to the principal woman dancer in a ballet company, or the highest ranking a dancer can achieve. This rank is rarely bestowed. There are only two ballerina’s in Russia that hold that title, Mathilde Kschessinskaya and Maya Plisetskaya. Two other dancers that were awarded this title are Alicia Alonso (Cuba) and Margot Fonteyn (England). No American ballerina has so far been granted this title, although it is said that Cynthia Gregory is deserving of this title.