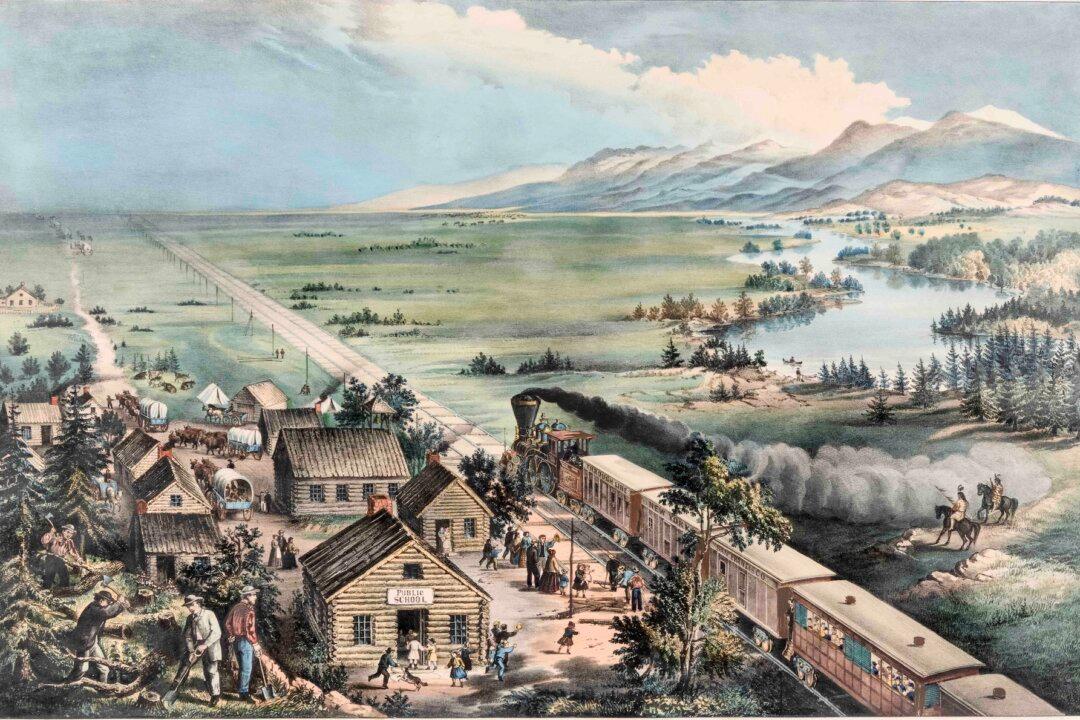

The impressive body of work by 19th-century lithographers Nathaniel Currier and James Ives is widely recognized today as hallmark Americana. Currier & Ives, as their business was known, specialized in producing inexpensive lithographic prints that were sold throughout the United States and in Europe, ranging from a couple dimes to $5, depending on size and intricacy. Before the days of widespread photography, many a home or office across America and beyond was decorated with the colorful lithographs that made Currier & Ives famous.

Lithography entailed producing illustrative prints from drawings made on a flat stone surface. From 1835 to 1907, the firm produced 7,500 lithographs and consigned millions of prints to vendors and agents in the United States and Europe. In so doing, the company became “the Grand Central Depot for Cheap and Popular Prints.” At the height of the two men’s success, 1850–1880, it is said their prints made up 95 percent of the market. The illustrations encompassed seasonal landscapes, urban and rural settings, the Rocky Mountains, the Mississippi River, architectural wonders, horse racing, gold mining, wagon trains, locomotives, clipper ships, steamships, and riverboats. They captured Revolutionary War scenes and, later on, Civil War scenes. They portrayed firemen, farmers, soldiers, hunters, housewives, businessmen, children, and families.