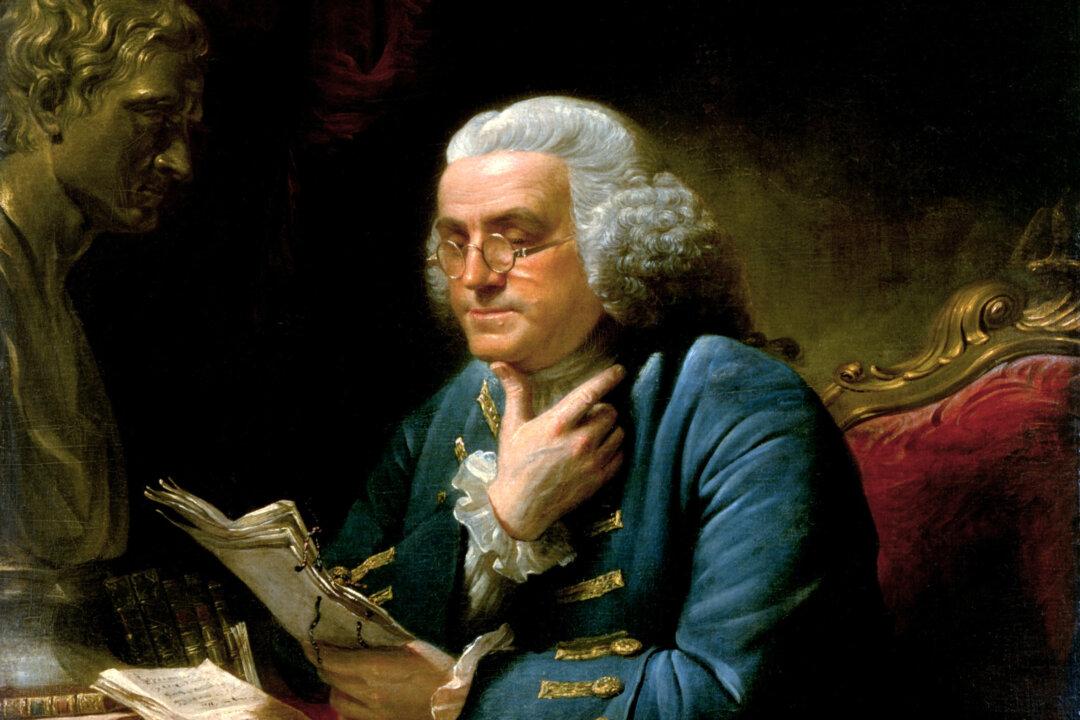

Among America’s founding generations, perhaps no one was as highly regarded as Benjamin Franklin—albeit George Washington was a close second. Both men came from humble beginnings, pulled themselves upward by their own initiative, and captured international esteem during their lifetimes by their service to country.

By the time they were in their advancing years, both men knew that their public image dwarfed their real personas by far.