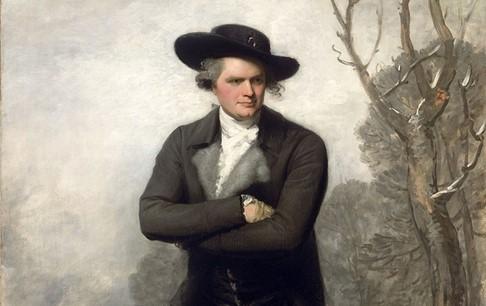

American captains of industry may have accumulated their wealth in less than honorable ways, but they did have good taste. They often used their newly acquired wealth to buy the best artworks the world could offer. Much of that art came from the private collections and museums of Europe.

Harry E. Huntington (1850–1927) was a railroad magnate who collected art, and the Duke of Westminster had a treasure that Huntington wanted: “The Blue Boy” by Thomas Gainsborough, painted circa 1770. When it came up for sale in 1921, Huntington outbid all comers and, for over $700,000, brought “The Blue Boy” to California in 1922.