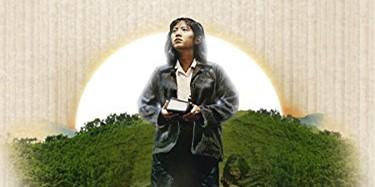

PG | 58 min | Drama | 1991

In late 20th-century China, a young college girl, Ah Choi (Crystal Kwok), graduates from university; 11 months later, she awaits a government placement that never comes. With no sign of a promising job in the city, she returns to her widowed father (Roy Chiao), her ailing grandma (Mary Walter), and farming in her village. Choi believes her mother died of an illness.