The clash between good and evil is as inevitable as the rising and setting of the sun. The specifics regarding this inevitability are many. On what scale will this clash be? Who will be on the side of good and of evil? Of those caught in the conflict, who will survive? Of those who survive, who will tell their story for the next generation? And of the next generation, who will listen?

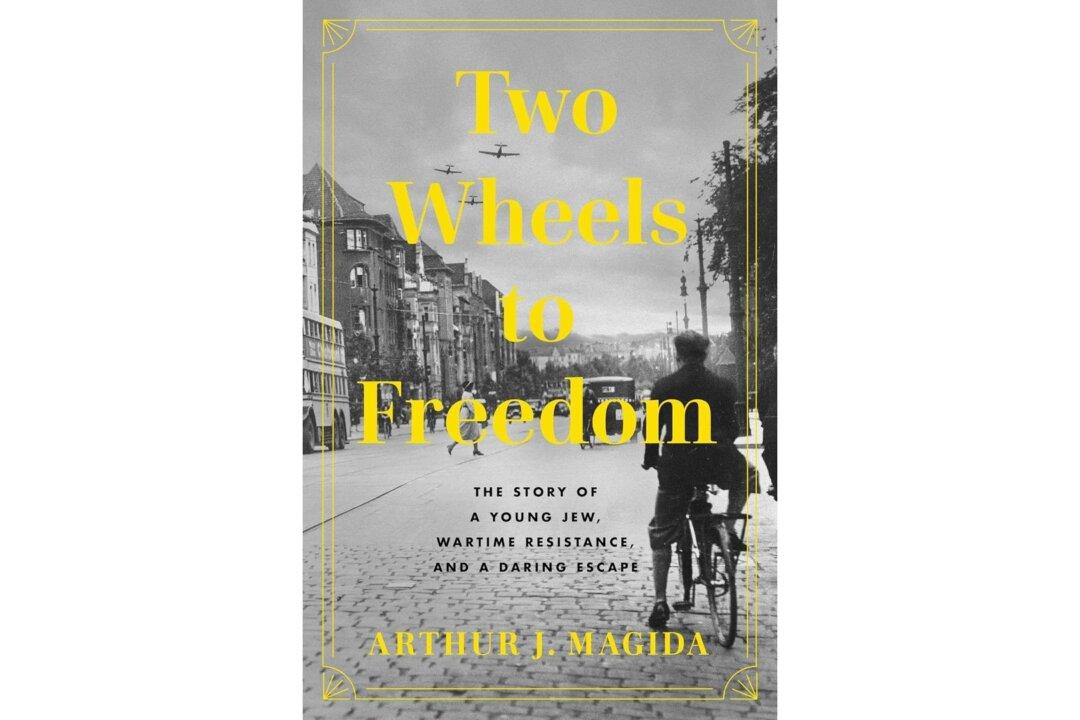

Arthur J. Magida has written a story told to him by a survivor from one of history’s greatest clashes: World War II. This survivor was a Jew caught at the heart of this struggle, in Berlin. “Two Wheels to Freedom: The Story of a Young Jew, Wartime Resistance, and a Daring Escape” is not a story warning future generations to settle differences and extinguish a clash before it takes place. That may be desired by the author, as it should be for any sane person, but this story is about surviving once it’s already too late.