When it comes to the three Punic Wars between Carthage and pre-empire Rome, the Second Punic War often takes center stage. The Second Punic War’s drama can’t be overstated. When these two mighty, practically equal powers went head-to-head, it produced two of history’s greatest military leaders: Carthage’s Hannibal Barca and Rome’s Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. It resulted in some of history’s most epic battles, like the much-studied Battle of Cannae and created the opportunity for the Carthaginians’ long, arduous, and odds-defying march over the Alps and into Italy.

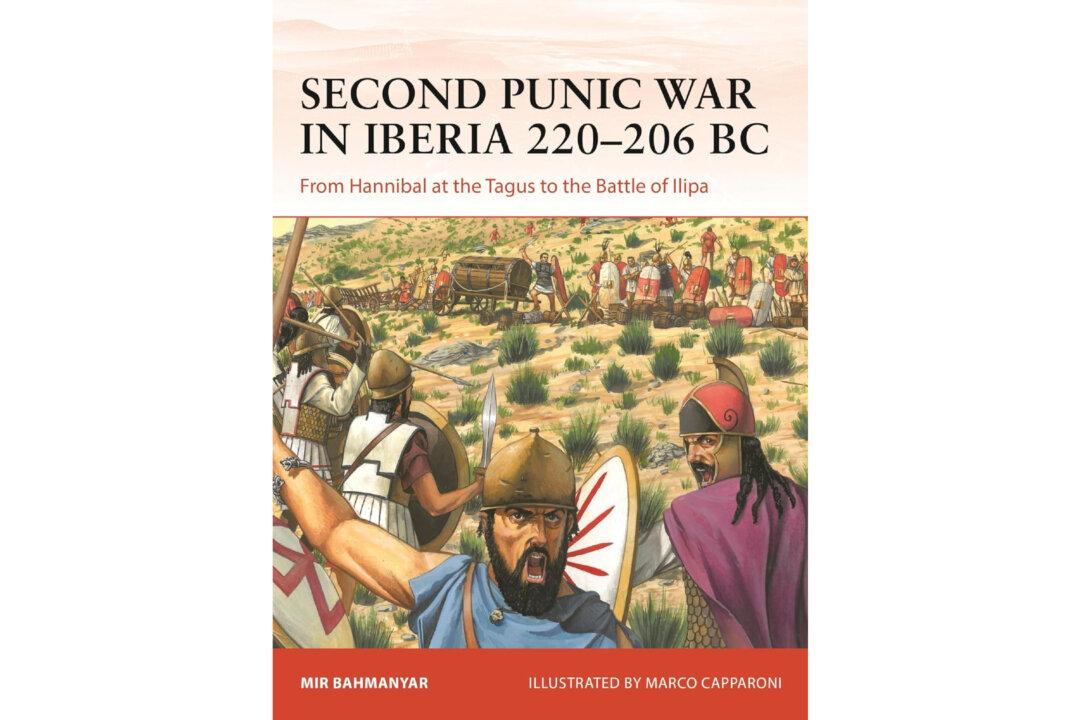

This war’s best remembered events took place in North Africa or Italy. Historians of the Second Punic War rarely attend as much to the Iberian peninsula (modern day Portugal and Spain). But Mir Bahmanyar, in his recent book “Second Punic War in Iberia 220–206 BC: From Hannibal at the Tagus to the Battle of Ilipa,” chose to illustrate just how important the battles, military leaders, and the peninsula itself were to the outcome of the war.