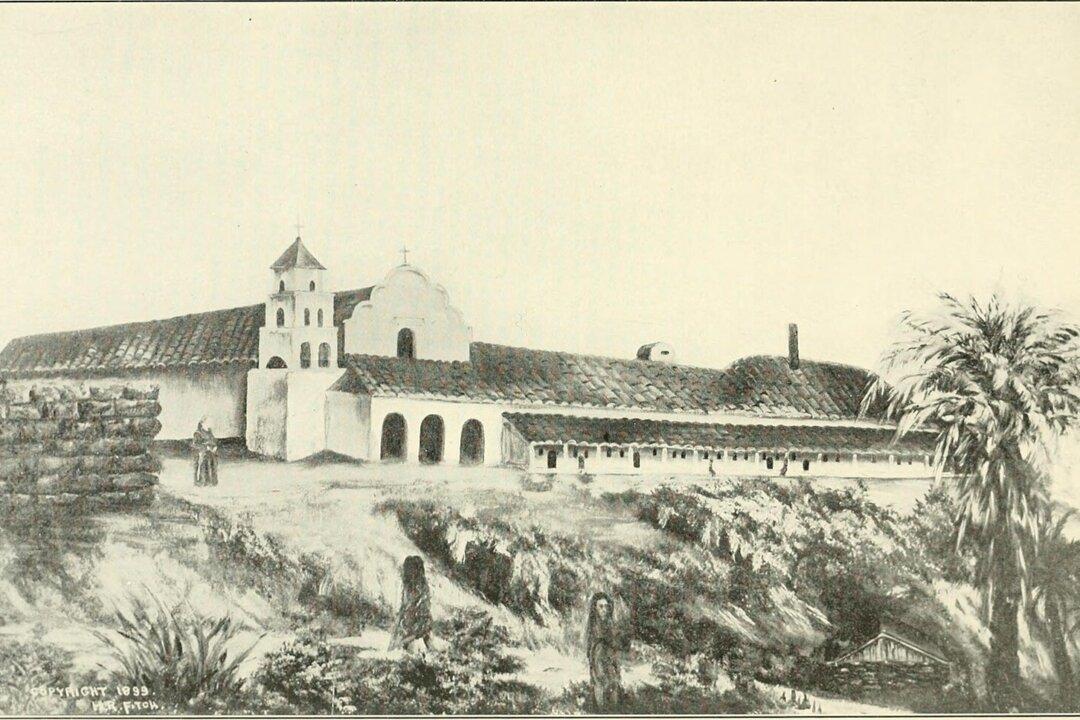

Many people have heard of the Presidio of San Francisco, but they aren’t as familiar with the Presidio in San Diego. Yet, high on a hill overlooking the city’s Old Town are historically significant grounds and an impressive structure worth exploring.

A Spanish word meaning a fort or settlement, “presidios” were built primarily for the protection of Spanish missions along the West Coast of the United States. The largest, now a National Park Historic Site, is in San Francisco and was established in 1776. Yet, on the opposite end of California, at the southern tip in the state’s second-largest city, is the site of a presidio that was founded eight years earlier.