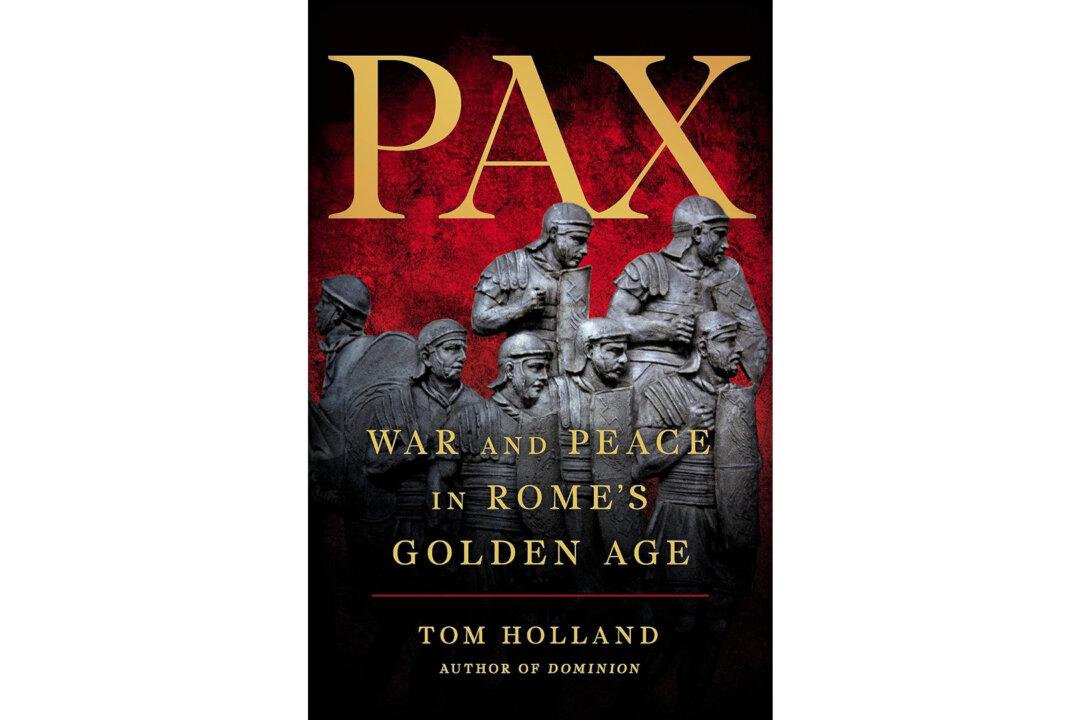

How did the Roman Empire get from Nero to Marcus Aurelius? Tom Holland, in his new book “Pax: War and Peace in Rome’s Golden Age,” takes the reader on a winding, bloody, chaotic, treacherous, perverse, and superstitious journey through the rise and falls of the 1st and 2nd century emperors.

Rome had experienced a century of peace after Caesar Augustus cleared away his enemies. This peace was internal, rather than external. After approximately a century of internal strife from Sulla’s civil war to Julius Caesar’s civil war to Augustus’s, the battles waged against outside forces certainly resembled peace for those inside Rome. But just as any country that endures civil war, much less multiple civil wars, Rome had changed. It had changed from a republic to an autocratic tyranny with a republican facade.