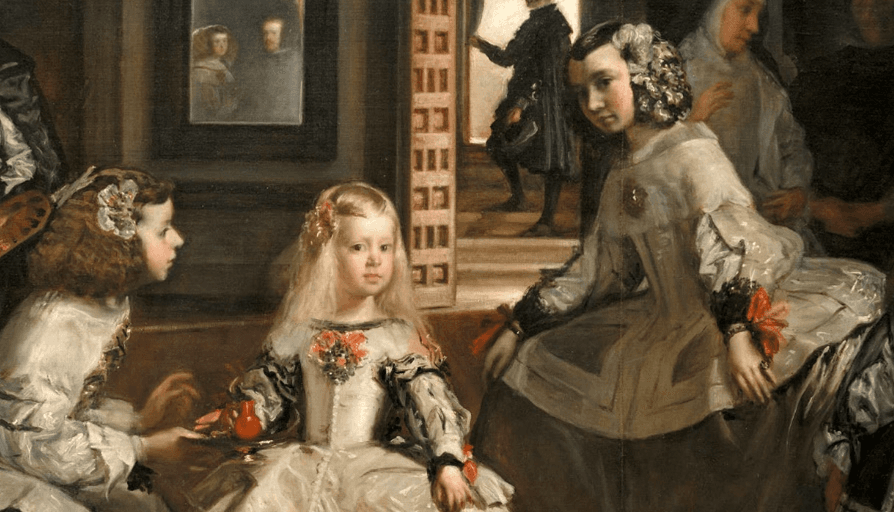

A child’s soft giggle echoes down the palace hall. Heavy skirts rustle. A lady-in-waiting enters and holds the door of the Cuarto del Principe (“Prince’s Room”) in the Alcázar Palace in Madrid, Spain.

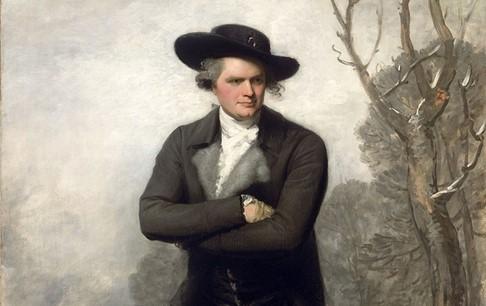

In comes a 5-year-old child, royal to be sure, to the spacious studio of the court’s chief painter, the eminent Diego Velázquez (1599–1660).