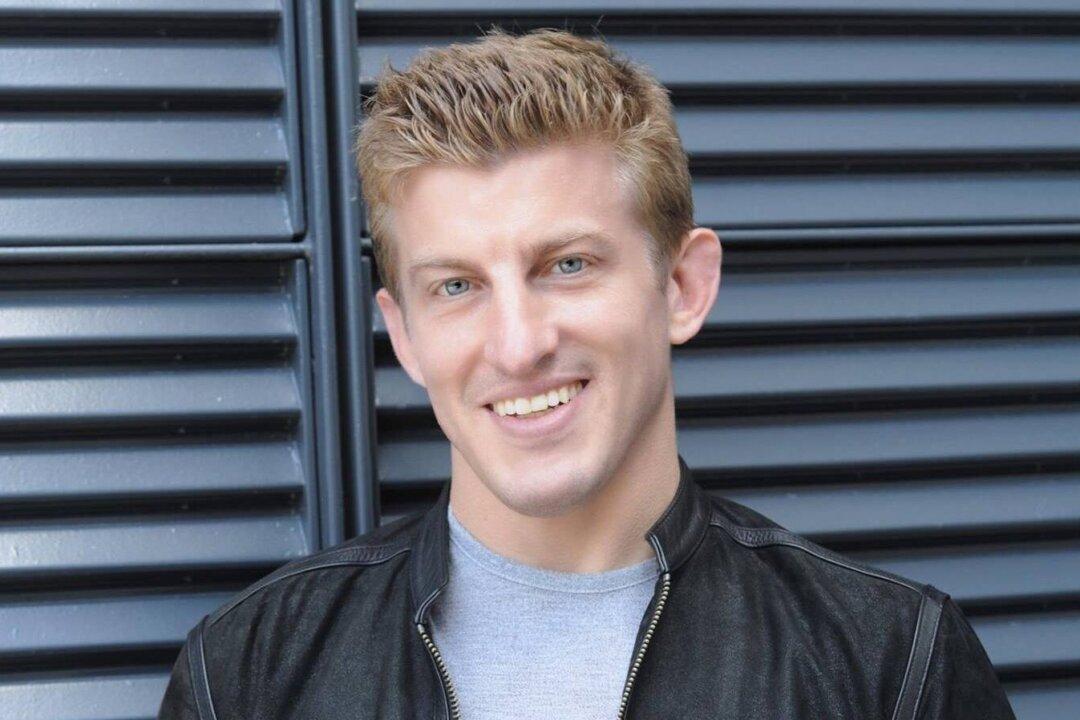

It’s easy to see why the legacy media has placed a target on Alex Epstein’s back: The “Fossil Future” author fights to win.

In the weeks leading up to the release of his latest book, The Washington Post planned to attack Epstein by labeling him a bigot. When Epstein learned about it beforehand, he struck first.