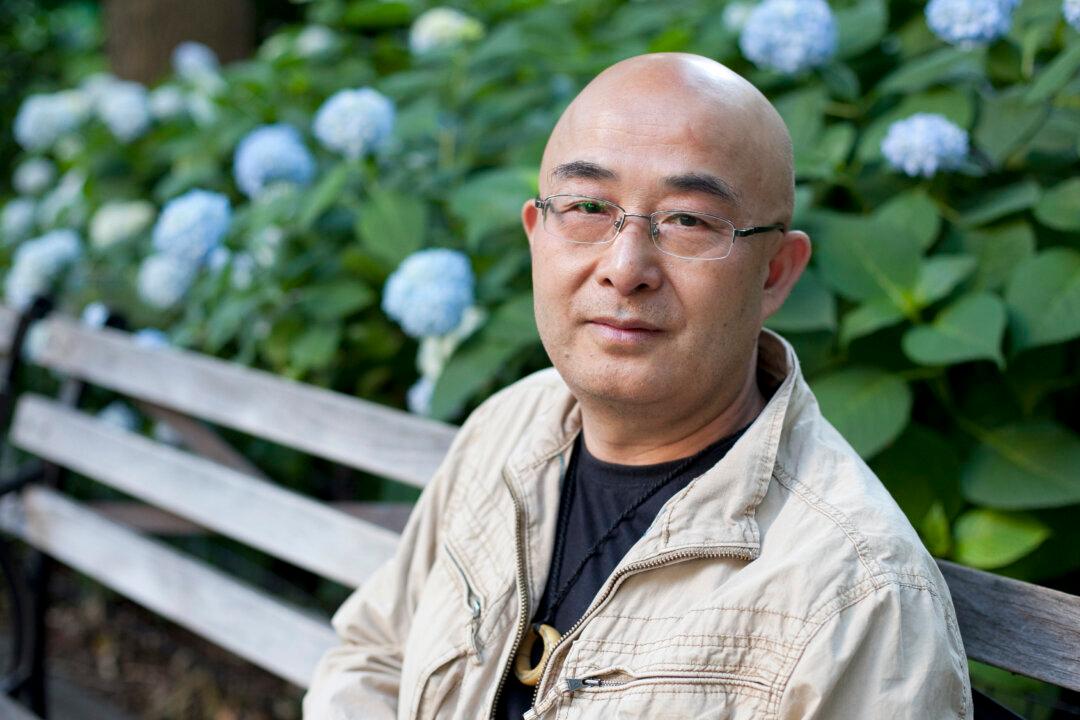

After Chinese dissident writer Liao Yiwu had his memoir confiscated by the police, he had to train his memory to become like a tape recorder, recollecting his experience in prison and the stories his fellow inmates had told him.

In 1990, Liao was sentenced to four years for writing a poem that condemned the Chinese regime’s 1989 crackdown on student protesters in Tiananmen Square. Knowing it would be impossible to publish it, Liao recorded himself reciting the poem, and the audiotape was spread around the country.

Liao would have to write his book three times before it was finally published as For A Song and A Hundred Songs. While in prison, he began writing the memoir on scrap pieces of paper that his family members would smuggle to him. But after his release, in 1995, the police raided his home and took away a year’s worth of writing. He then began work on the book from scratch, but the police confiscated his manuscript in 2001. It wasn’t until 2011 that he smuggled the book out of China and finally had it ready for publication in Germany and Taiwan. On June 4, the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, Liao’s memoir was released in the United States in English translation.

“I suspect that a lot of the details from when I was in prison have been forgotten, but there were also new details that would emerge, so I’m not sure which draft was the best,” Liao said in an interview in New York, ahead of his appearance at an event celebrating the U.S. publication of his memoir.

In 2011, Chinese authorities knocked on his door again, this time threatening that if he were to publish his memoir, he will get locked up again, this time for at least 10 years.

He decided it was time to leave the country. In July 2011, he arrived in Germany, having escaped through Vietnam with the help of several friends.

Liao said he had no choice but to write this book. “If you don’t, then that whole prison experience, that part of history will be forgotten. It’s very frightening. You not only have to be tormented, but you also have to suffer the pain of being forgotten, then you'll turn into a piece of junk.”

While in prison, Liao was tortured, both physically and mentally, which he recounts in detail in his book. The title of the volume refers to one episode when a prison guard punished Liao for singing a song by asking him to sing 100 more. When he couldn’t continue anymore, the guard stuck an electric baton into his anus. “I felt like a duck whose feathers were being stripped,” Liao wrote.

His inmates—which included murderers, rapists, thieves, and human traffickers—also told him stories of their exploits. Having been a bohemian poet for most of his life prior to becoming a political prisoner, being in prison exposed him for the first time to “an underground China, a China that doesn’t see the light of day,” he said.

As he listened and committed to memory these people’s stories, he saw a darkness he never saw before. “Why did so many people become criminals? Although they have committed crimes, oftentimes it was because they were forced until they had no choice,” he said.

Liao began to understand that there was a problem with Chinese society at large. “For some people it was because of a simple act of resistance, that they decided to murder someone, that they took risky actions, after having nowhere else to turn to. For some, it was because they couldn’t survive anymore, so they turned to stealing.”

It was then that Liao took interest in recording the stories of people on the margins of society. (Later, Liao would conduct interviews with these individuals, compiling their stories into the book, The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories: China from the Bottom Up).

Liao said: “My prison experience changed me from being a poet to being a witness of history, a tape recorder of an era. I now consider myself a tape recorder. To record suffering is a writer’s first and foremost [task].”

After Liao was released from prison, he realized that the outside world was like “a prison without walls.”

“Chinese society gathers together man’s evil, unlike in the West, where they can limit this kind of evil through institutions, laws, or religion. It’s the opposite in China,” Liao said.

Although Liao is critical of the Chinese regime—most famously announcing that “this empire must split apart” in his address for winning the 2012 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade—Liao does not consider himself a political writer. Instead, he believes he is merely a chronicler of truth, of people’s stories.

“I don’t have any political views. The difference between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and I is an aesthetic one.”

He explained: “Pigs at least have a better sense of beauty; after they have eaten their full, they let out sounds of happiness and satisfaction, and they don’t disturb anyone, they just go to sleep. But the CCP, after they have eaten and taken all they want, they treat others with cruelty and brutality.”

He said that he hoped American readers can see for themselves the conditions of the prison system in China, and that the atrocities in the book are still happening today. “If they still want to do business with the CCP, they should really ask their conscience, is this good for the common people of China?”

Now a celebrated author in the West, Liao reflects on his days in China when his books were banned and sold in underground markets. “I finally turned from a hidden enemy of the state, to become a public enemy,” Liao said, chuckling. “I consider it my honor.”