“Hamlet” is arguably the most famous of William Shakespeare’s plays. It is the source of such famous lines as “To be or not to be—that is the question,” “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” “Brevity is the soul of wit,” “To thine own self be true,” and the list goes on and on.

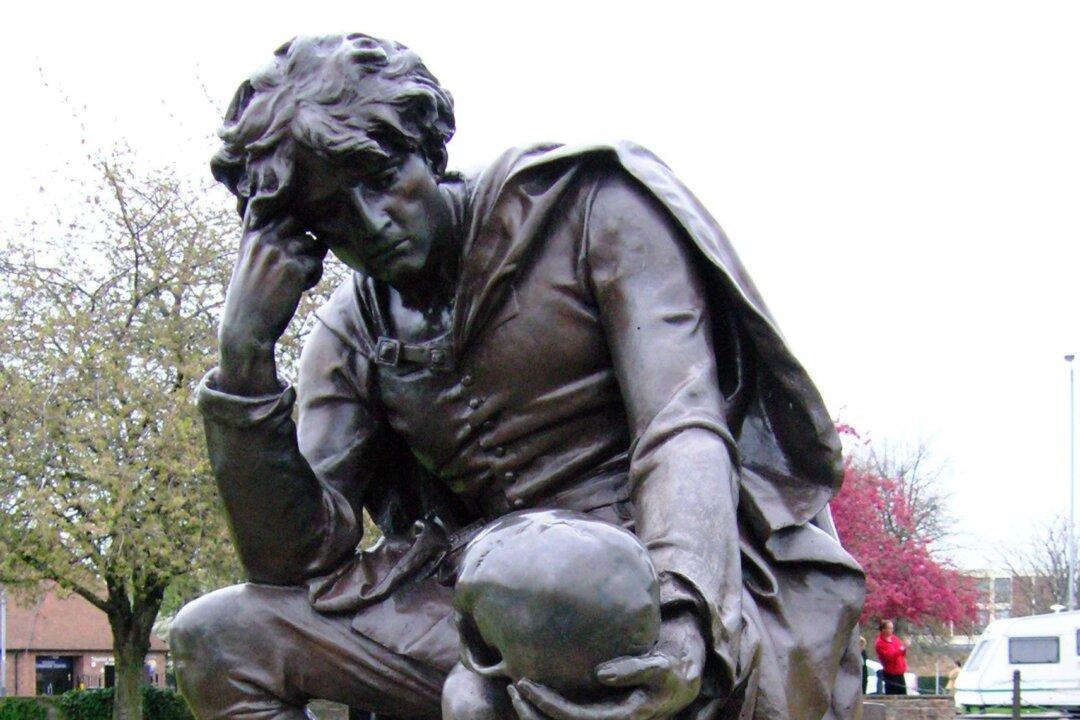

The famous skull that often appears in caricatures of Shakespeare comes from “Hamlet.” I also find my children watching current TV shows that feature “Hamlet”-themed episodes and, of course, Disney’s “Lion King” takes some plot points from the play. According to the British Council, “Since 1960, there have been publications and productions of ‘Hamlet’ in more than 75 languages.”