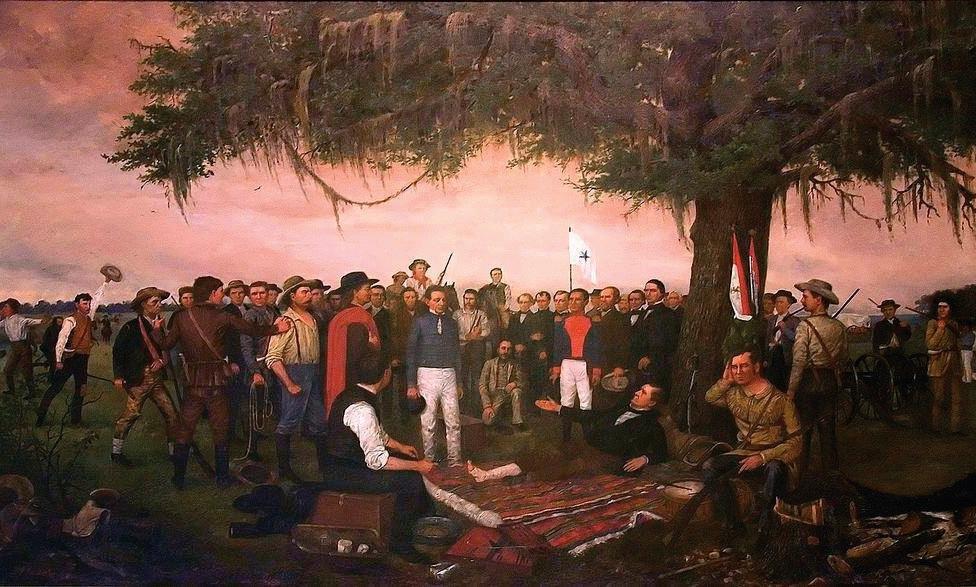

Gen. Sam Houston rested under an oak tree on the coastal plains of Texas near Buffalo Bayou, his left ankle shattered by a copper ball. He and his Texian army of 783 men had just defeated a Mexican army detachment of about 1,500 soldiers under the command of Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna, president of Mexico. When Houston gave the volunteer army its war cry of “Remember the Alamo,” the Texians struck their enemy like a bolt of fire in a surprise attack on April 21, 1836, near the San Jacinto River in southeast Texas.

The Battle of San Jacinto went down in history as a day of vengeance, as the soldiers sought retribution for the massacres in San Antonio de Bexar and Goliad the month before. The clash lasted only 18 minutes; the Texas Revolution was now complete after months of multiple conflicts and bloody battles. The Mexican state of Tejas won its independence from Mexico and became the Republic of Texas.