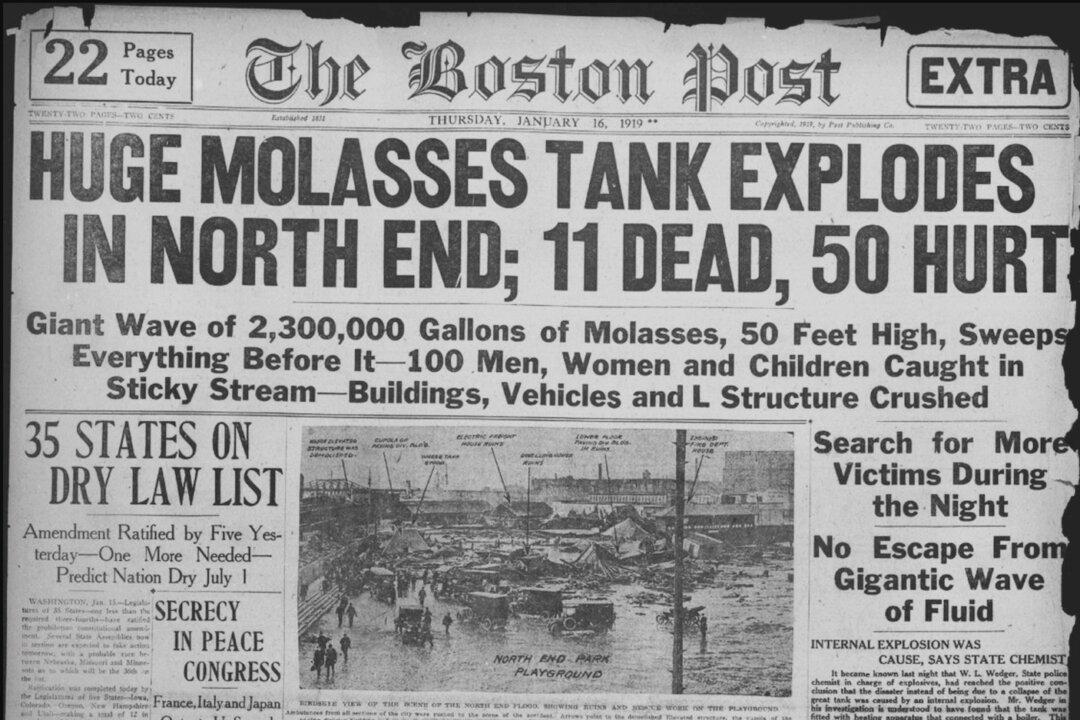

“Send all available rescue vehicles and personnel immediately,” Boston Police Patrolman Frank McManus managed to relay to dispatch through the call box located on the North End near the harbor. A bizarre tragedy was unfolding before his eyes and momentarily left him speechless. “There’s a wave of molasses coming down Commercial Street.”

As the policeman began his routine midday report, he heard a sound resembling the rat-tat-tat of a machine gun. He had no way of knowing it was rivets popping from the seams of the giant, 50-foot-high and 90-foot-wide molasses tank holding more than 2 million gallons of the dark, sweet, syrupy liquid. When the tank burst, it set in motion a black tidal wave that was 160 feet wide and reported to be anywhere from 15 to 40 feet tall.