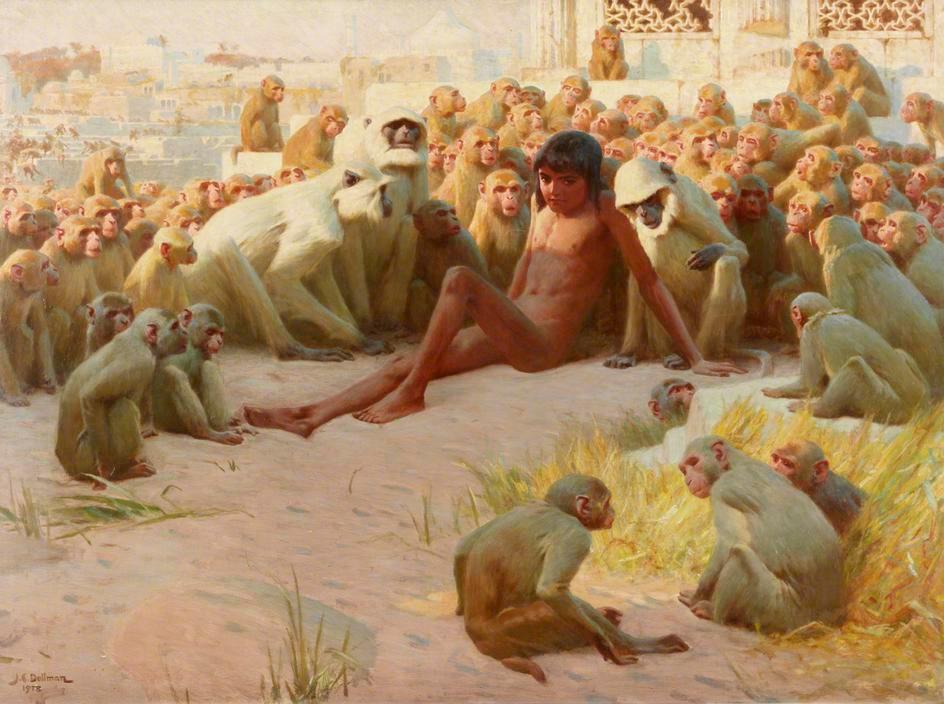

I once attended a lecture on Plato’s “Republic,” in which the lecturer pointed out how Socrates argues that poets should be banned from the ideal city as they employ arts that stir the passions too much and aren’t as precise and perfect as the rational arts. A heavy condemnation. And what defense can Poetry make for herself, the professor asked. How can she justify her existence in the face of such logical dismissal?

Then he did something completely unexpected and wonderful. Standing at the podium with a twinkle in his eye, he began then and there to sing the old Scottish song “Loch Lomond.” As he sang, “Oh, ye’ll tak the high road and I’ll tak the low road,” other voices joined in the familiar tune until the whole audience was singing with him.