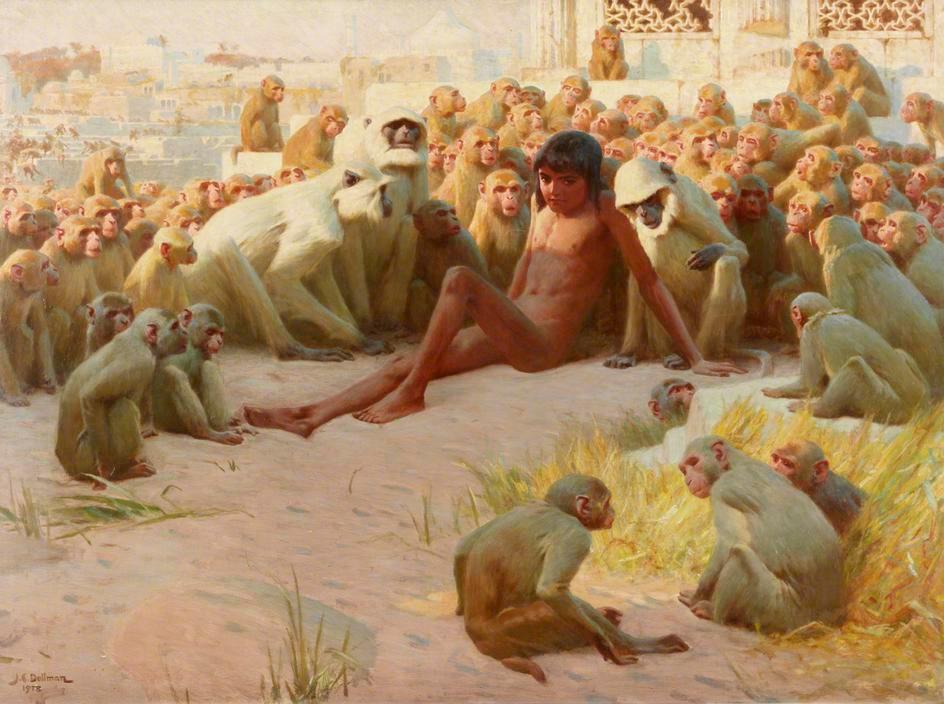

The world bound up in the snow and ice of winter is as fascinating as it is forbidding.

Hoary mountains, blinding blizzards, snowy deserts, solid waters, fluid fires of the aurora borealis, and air that stings to breathe all give the distinct impression that men ought not keep company with such inhospitable presences.