I’ve known ere now an interfering branch Of alder catch my lifted axe behind me. But that was in the woods, to hold my hand From striking at another alder’s roots, And that was, as I say, an alder branch. This was a man, Baptiste, who stole one day Behind me on the snow in my own yard ...

Picture this sequence of events: You’re out cutting firewood, a neighbor walks up behind you, grabs the axe while you’re at the bottom of your swing, and then ... that evening, you’re at his home talking about homeschooling. A little strange, no? But that is a summation of the action in Robert Frost’s poem “The Axe-Helve.”

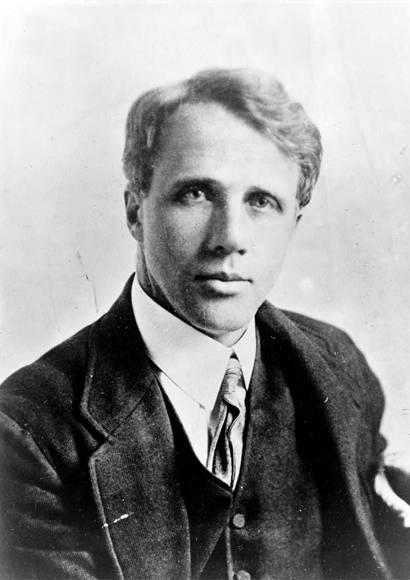

Robert Frost often depicted rural life in his poems. The poet in the 1910s. Public Domain