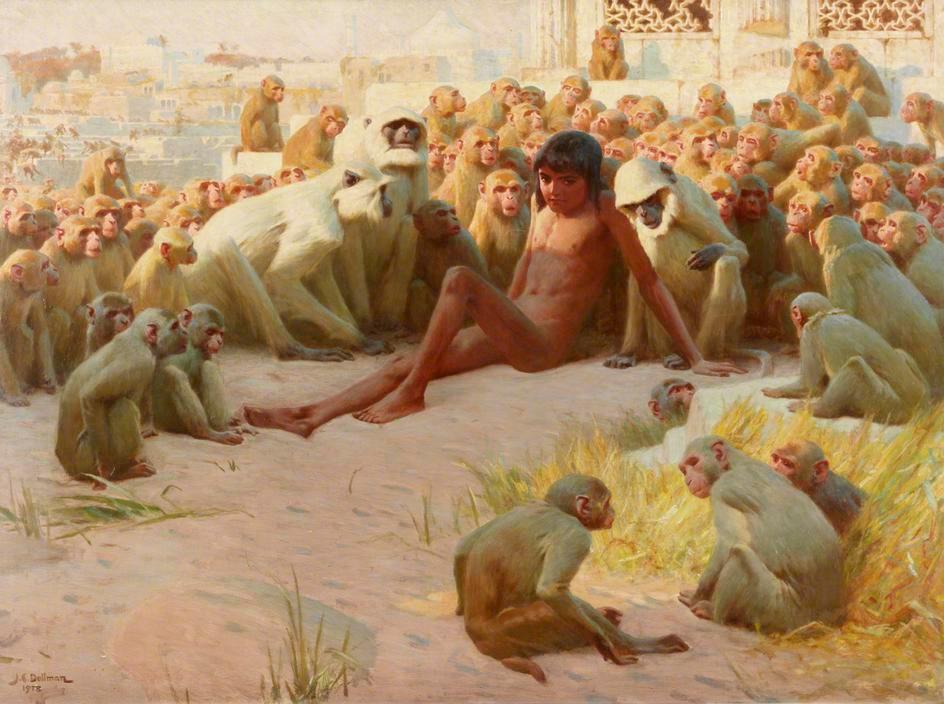

Even in the awakening of new life in springtime and in Eastertide (the time that stretches beyond Easter), there comes the sweet yet sad reminder of the fleetingness of things, that all that lives must die. This is a favorite subject of poetry.

The freshness of spring is all too brief, as Robert Frost’s famous poem laments. He says at once, “Nature’s first green is gold” and “Nothing gold can stay.” Gerard Manley Hopkins has a similar sadness in “Spring and Fall,” where we sense the inevitability of death in the seasons.