No matter which major party won America’s presidential election in 1920, the country was destined for another chief executive from Ohio. Both major party candidates, Republican Warren Harding and Democrat James Cox, hailed from the Buckeye State.

Warren Harding’s Historic Speech on Race: How Black and White Americans Responded

When the president finished, the cheers all came from the back

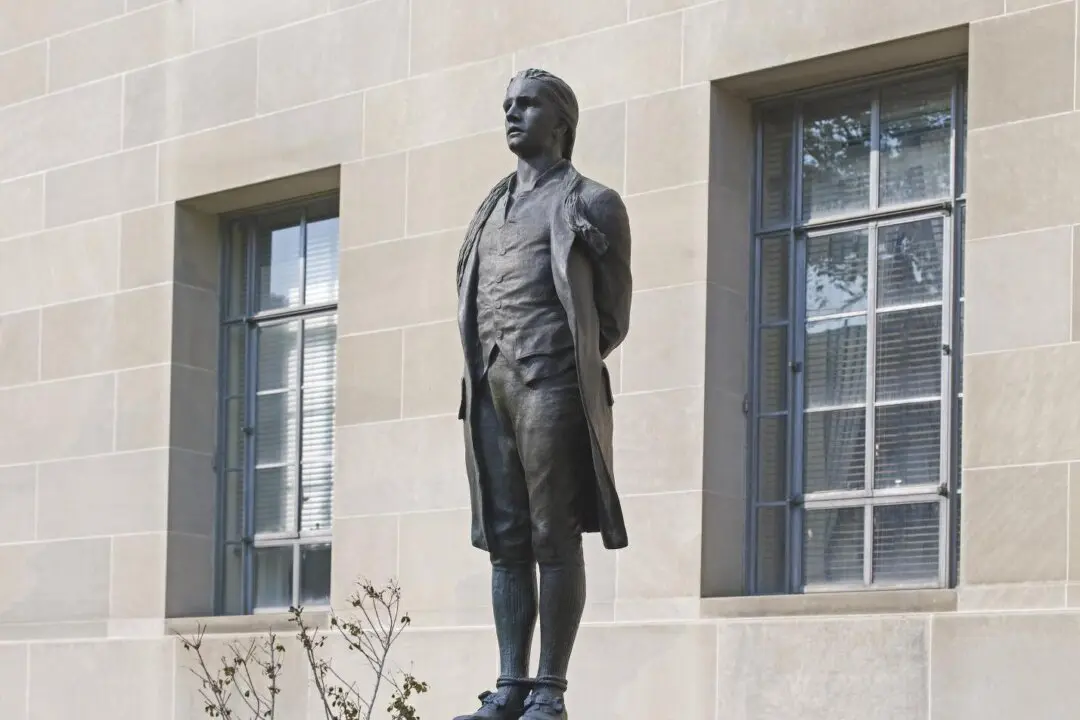

Warren G. Harding (1865–1923), when he was a U.S. Senator from Ohio in 1920. He became president in 1921. FPG/Getty Images

|Updated: