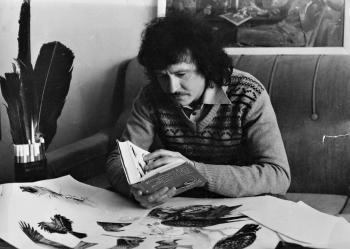

With a Cheshire cat-like grin, Victor walked me through his studio. Suffering from an injury he sustained in his youth from a climbing accident, he cradled his arm. Allergic to pain medication, he would wince a little bit and carry on.

A front was blowing through, perhaps agitating his old injury. In any case, the winds outside his studio in a high building above Madison, Wisconsin, were blowing in spring.

Victor Bakhtin was born and raised in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk. He was enthralled with the wild, and his eagerness and love of life led him to live life in full color. Now a world-class nature artist, many of his paintings are hanging in Holland, Sweden, Spain, England, South Africa, Japan, Taiwan, and the United States.

Originally set on being a violinist, a tragic climbing accident in his youth made it impossible for him to pursue music. Before the accident, the highly energetic Victor had a hard time sitting still.

Vladimir Zykov, a former colleague who had worked with Victor at the Krashnoyarsk Publishing House, remarked, “I can’t remember a day he would spend at his desk from 9 to 6.”

He was always getting into trouble. The publishing-house director often “lost” him and loudly expressed his indignation at the lack of discipline in his young worker. However, when the printers urgently needed a stamp, Victor got to work and astonished the director.

Starting as a technical editor, then an illustrator, Victor made his mark by illustrating some 78 books. He also began publishing his caricatures, or cartoons, in local newspapers in Russia.

A front was blowing through, perhaps agitating his old injury. In any case, the winds outside his studio in a high building above Madison, Wisconsin, were blowing in spring.

Victor Bakhtin was born and raised in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk. He was enthralled with the wild, and his eagerness and love of life led him to live life in full color. Now a world-class nature artist, many of his paintings are hanging in Holland, Sweden, Spain, England, South Africa, Japan, Taiwan, and the United States.

Originally set on being a violinist, a tragic climbing accident in his youth made it impossible for him to pursue music. Before the accident, the highly energetic Victor had a hard time sitting still.

Vladimir Zykov, a former colleague who had worked with Victor at the Krashnoyarsk Publishing House, remarked, “I can’t remember a day he would spend at his desk from 9 to 6.”

He was always getting into trouble. The publishing-house director often “lost” him and loudly expressed his indignation at the lack of discipline in his young worker. However, when the printers urgently needed a stamp, Victor got to work and astonished the director.

Starting as a technical editor, then an illustrator, Victor made his mark by illustrating some 78 books. He also began publishing his caricatures, or cartoons, in local newspapers in Russia.