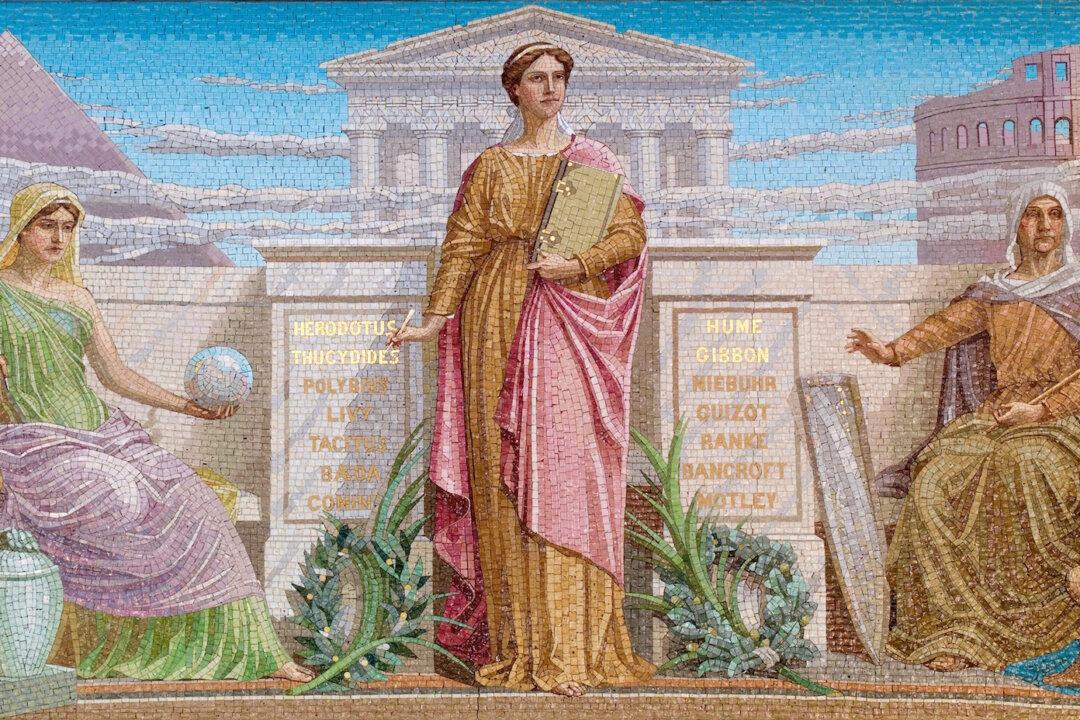

If there is anything the Founders constantly repeated, certainly one of the most important was the importance of studying history. After all, humanity has been around a lot longer than any of our lifetimes. Our species has thousands of years of experience under its belt. It stands to reason there’s a lot of wisdom to be learned by studying it. That’s what our Founders did, and it’s why they insisted that future generations must do the same in order to preserve our institutions.

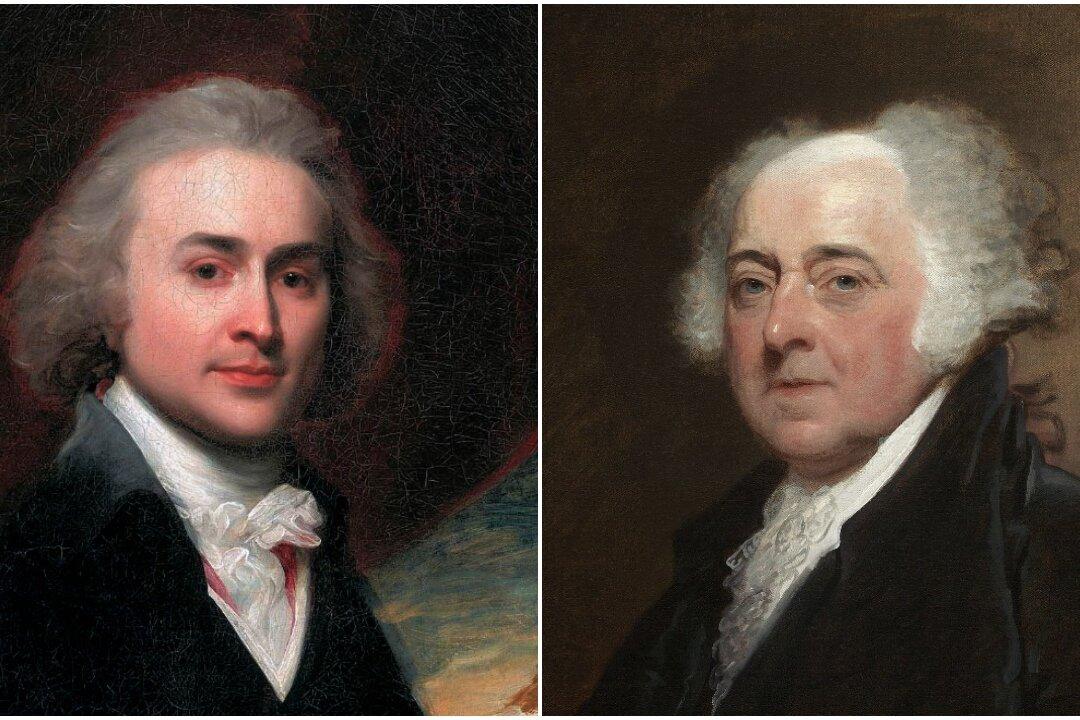

James Madison, for example, called history “an inexhaustible fund of entertainment and instruction.” Indeed, he, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, drew from this “inexhaustible fund” in their great work, The Federalist Papers. It was from that “inexhaustible fund” the Founders drew when they designed our Constitution, and the reason it remains the oldest living written Constitution in history.