Ottawa’s Music and Beyond festival has long embraced the traditional along with the unorthodox. Sometimes these two worlds collide in an extraordinary way when an artist uses a modern instrument in a classical setting. Such is the case with Theremin player Thorwald Jørgensen.

The Netherlands native is a master of the theremin, a musical instrument that is played using only hand gestures to produce a unique sound that has a haunting, ethereal quality in a seven-octave range.

So how exactly do you play a musical instrument without touching it?

The theremin is a small cabinet with two antennas: a vertical metal rod for controlling pitch and a round one for adjusting sound level.

Inside the cabinet are oscillators, one at a fixed frequency and another whose frequency is controlled by the distance of the player’s hand from the vertical antenna. It is the difference between the two frequencies moment to moment that changes the audio frequency tone. The resulting audio signal is amplified and sent to the speakers.

The position of the fingers of the player’s right hand relative to the rod produces the various notes, while side to side hand movements produce vibrato. The player’s left hand moves up and down over the round antenna to control volume. This setup can be reversed depending on the player’s preference.

In the end it looks like the music is being produced from thin air.

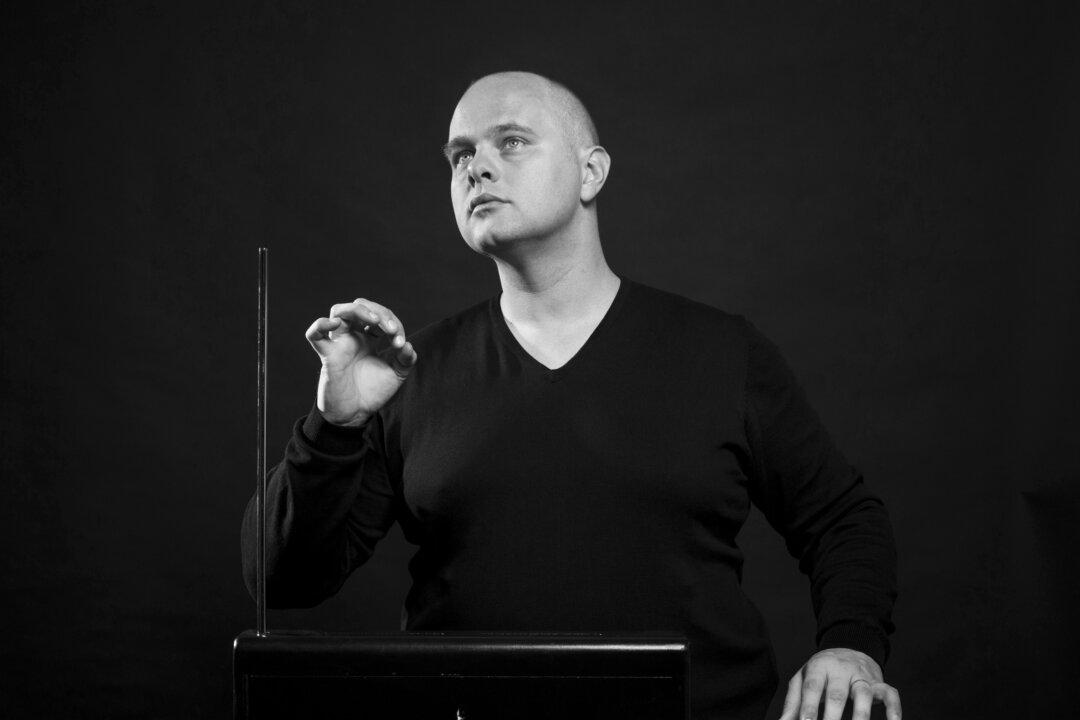

Jørgensen playing Bachianas Brasileiras no.5 by Villa Lobos with harpist Renske de Leuw

Jørgensen started studying classical percussion when just 14. Within a year he was playing with orchestras. After graduating from the Utrecht and Tilburg Conservatory he became a percussionist in a provincial orchestra. Although he still plays with the orchestra he felt he wanted to be centre stage and play full melodies, not just interspersed percussing of short duration.

Around this time he heard Clara Rockmore, a theremin virtuoso from the 1930s and ‘40s, and fell in love with the sound. He thought she was playing a violin. When he learned that she was playing the theremin he researched it and decided he would learn to play it.

“When I found the theremin I became obsessed with it,” he said. He bought his first instrument and could play it right away.

“I immediately had a natural feeling for how it worked. Then I practised for six months. After six months I got my first concert with a symphony orchestra.”

Pulling an Invisible String

Eventually, he sought tutoring from a cellist friend who told him his playing method was wrong. She helped him refine his technique by comparing the hand movements that control the notes to pulling an invisible string.

It is the seemingly pulling an invisible string and thereby producing beautiful music that evokes a jaw-dropping reaction in people who see the theremin played for the first time. To some it looks like magic or trickery.

Jørgensen sees it as an instrument in its own right.

“I think that the theremin has its own musical qualities and its own place in the musical field. It has its own sound and its own repertoire. I think it is very important that music is written for the theremin,” he said.

“What I found interesting is the sound of the instrument because if played well it can sound—even though it’s a 100 percent electronic instrument—like it’s almost human or an acoustic instrument. I never heard any other electronic instrument with that quality, that life-like quality. It’s really alive.”

Jørgensen said he starts each recital with one of his favourite pieces, Rachmaninoff’s “Vocalise.”

“After that I always explain the instrument, because if I don’t people tend to only look at what I’m doing instead of listening to the music. It should be about the music and not about me playing in the air,” he said.

It is a difficult instrument to play well, and players need to control their body and breathing as such movements can cause the sound to be off-key. Jørgensen said he stands a certain distance from the conductor and the violinists in an orchestra as their movements can also interfere with the pitch.

He said he uses his face rather than his body to express emotions while playing the music.

Jørgensen will perform July 12 through 16 at six venues during Music and Beyond. At his July 16 recital, a cocktail reception at the Diefenbunker, he will be accompanied by Daniel Desmarais on piano and will premiere “The Awakening of Baron Samedi,” written for him by Canadian composer Daniel Medizadeh.

Music and Beyond runs from July 5 to 17. For more information, visit: www.musicandbeyond.ca