Imagine yourself at a flea market or antique shop. You find an old leather-bound book, its spine slightly cracked with dusty, yellowed pages inside. The book doesn’t have a title or author mentioned, so you open it up to see what’s inside.

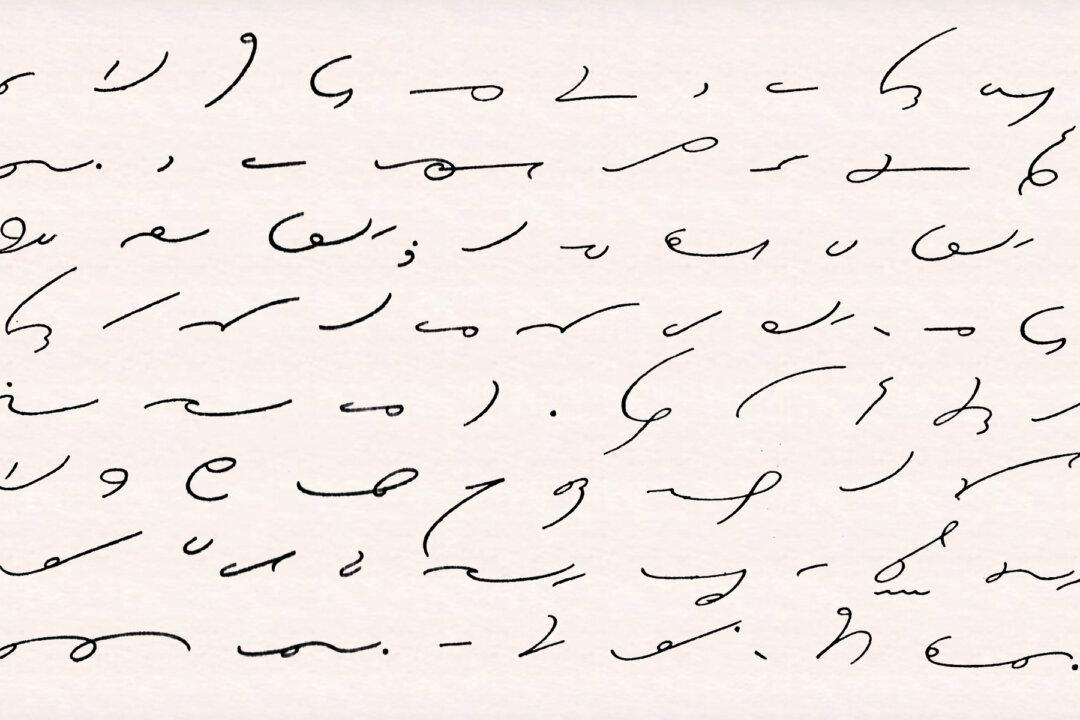

What awaits you is something stranger than you’ve ever seen. Small, curved lines with curlicues and little eyes, and occasionally some dots or dashes. It looks like some kind of writing system, but not one that you’ve ever seen. Some of the scrawling looks a bit like the cursive that you had to learn as a kid at school, the big loops and squiggles.