How many times have we heard praises sung for “the common man” or “the common woman”? Far more than I can count, and it bothers me every time the phrase comes up. Why? Because it is not the common to which we owe our highest gratitude. That honor belongs to the uncommon.

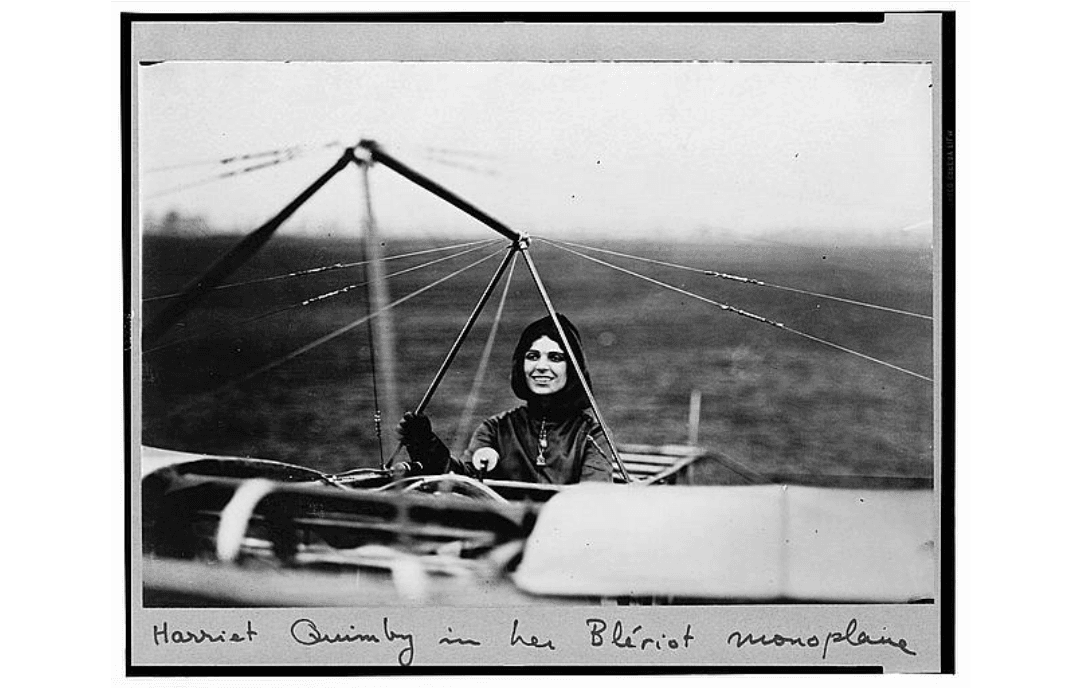

Bessie Coleman set her sights on becoming a pilot. She became a sensation as a barnstorming stunt flyer. Public domain

|Updated: