“It was traditional in Maine when I was growing up. Most families had baked beans and brown bread Saturday nights. My mother used to make it for us,” soon-to-be 100 years old Lt. Armand Sedgeley said.

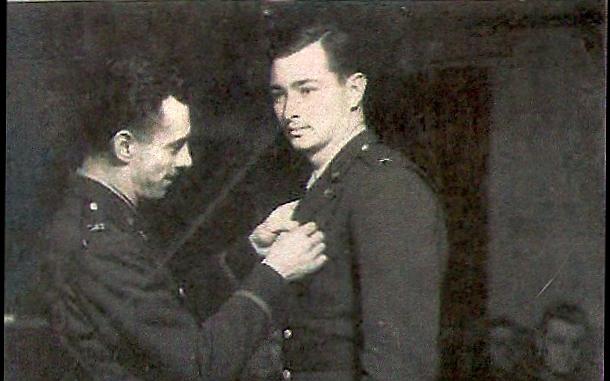

This World War II hero is now in hospice care just outside of Denver. How I came to know him is as intriguing as his bravery on Feb. 14, 1944, when, while on a mission to bomb enemy rail yards in Verona, Italy, his B-17 was attacked by five Nazi Messerschmitts.