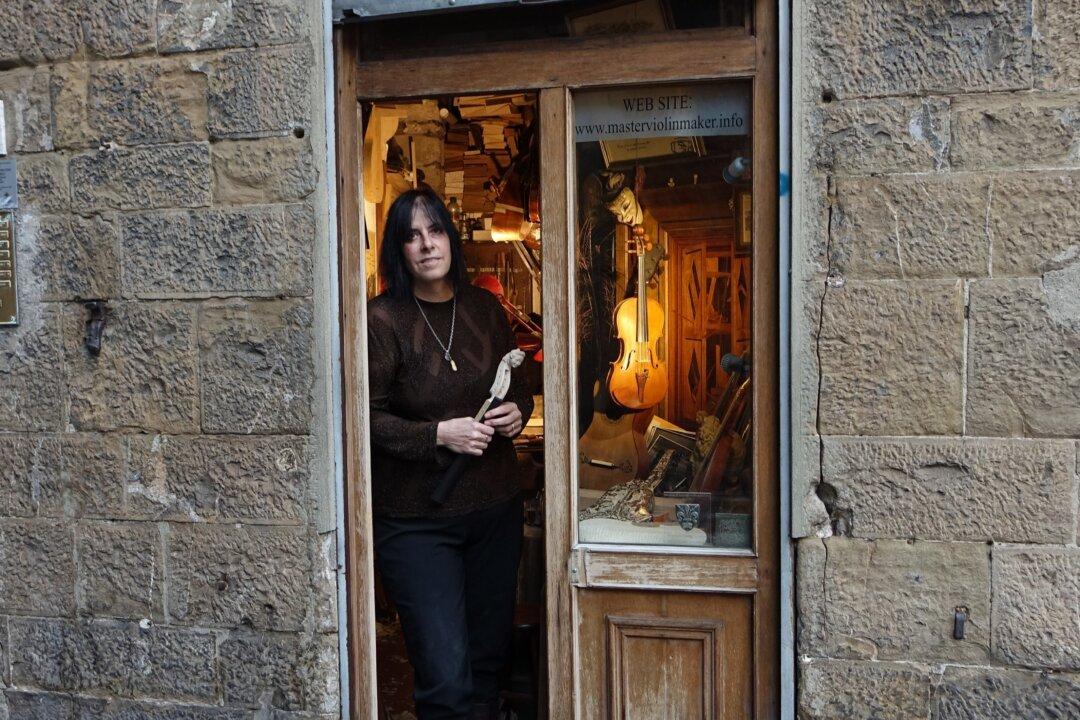

FLORENCE, Italy—If you are lucky, you may hear this workshop before you see it. Dulcet sounds have been known to waft from within this tiny workshop’s walls, in a way that literally stops traffic. Follow the melody and you’ll find Chicago-born Jamie Marie Lazzara, a master violin maker and restorer of fine stringed instruments, perfecting one of her handcrafted violins. If you’re really lucky, the sound may be emanating from the violin of one of her clients, among whom are the world’s renowned violinists Itzhak Perlman, Micha Molthoff, and Sarn Oliver.

Such famous clientele recognize Lazzara’s high-quality traditional instruments, as does Florence. In the entrance to her workshop hangs a parchment from the Society of St. John the Baptist, an honor from the Medici family that Lazzara states is one of the highest honors an artisan can get in Florence. The paper recognizes her 40-year-old workshop as a historic shop where everything is done entirely by hand, in the spirit of art conservation, using antique procedures of the great master violin makers of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. It further acknowledges Lazzara’s work of meeting the needs of soloists today.